Tomorrow I hope to post a brief response to the recent camel story with a number of links to helpful stories that provide a perspective not provided in the mainstream press. Today I want to summarize some interesting analysis from a less accessible article. (After I wrote this, I located it online at Academia.edu, but it is still less accessible to most readers by virtue of its length and sometimes-technical discussion.)

Written by Martin Heide of the Philipp University of Marburg, the article was published in 2011 in Ugarit-Forschungen. The title is “The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible.”

The following observations include direct quotations as well as my summaries. In places I have added a comment of my own following the page reference.

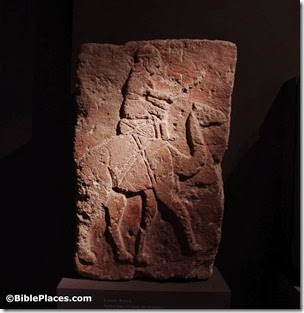

Rider on dromedary camel, relief from Tell Halaf, 10th-9th c BC

Photo by A.D. Riddle; on display at Walters Art Museum

On the problem of negative evidence:

“Proving that something did not exist at some time and place in the past is every archaeologist’s nightmare because proof of its existence may, despite all claims to the contrary, be unearthed at some future date” (337). Many have said similar things, but I like his choice of words.

“The camel is never mentioned in any Egyptian text known today” and yet we have evidence for camels in ancient Egypt (342). The lack of evidence to support a theory must be used with caution.

We should not be surprised that there is limited archaeological and inscriptional evidence from urban areas when camels were primarily used outside of such (354).

We don’t know when or where the dromedary (one-humped) camel was domesticated (361).

Even in a later period in Mesopotamia when camels were in widespread use for trade and military purposes, there are very few references to it outside of campaign reports (369). The use of camels by the patriarchs would have been unrecorded even in a time when we have many references to their existence.

On evidence for camels before 1000 BC:

The two-humped (Bactrian) camel was in use in southern Turkmenistan not long after 3000 BC. It was the standard for the region by the second half of the third millennium (344). Abraham lived after this time, and it is not difficult to imagine that other peoples recognized the value of camels and used them. The debate is partly between the positive evidence (attestation in the biblical record) and negative evidence (limited evidence in excavations and inscriptions).

A Sumerian love song from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 BC) mentions the milk of the camel and is best taken as referring to a domestic camel (356-57).

Evidence for Mesopotamian use of domesticated Bactrian camels includes two lexical lists from the

Old Babylonian period “and probably also by the Sumerian tablet mentioning the GÚ.URU×GU and the cylinder seal from the Walters Art Gallery” (358). A photo of the cylinder seal can be seen here.

“To sum up the early evidence, it is certain that based on archaeological evidence the domesticated two-humped camel appeared in Southern Turkmenistan not later than the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE. From there or from adjacent regions, the domesticated Bactrian camel must have reached Mesopotamia via the Zagros Mountains. In Mesopotamia, the earliest knowledge of the camel points to the middle of the 3rd millennium, where it seems to have been regarded as a very exotic animal. The horse and the Bactrian camel may have been engaged in sea-borne and overland global trading networks spanning much of the ancient world from the third millennium BCE onwards” (359).

Limestone camel vessel from ca. 3000 BC

Photo by A.D. Riddle; artifact on display in Berlin Egyptian Museum

On the biblical text:

We need not assume, as some do, that Abraham was given camels in Egypt (Gen 12:16). Rather it seems best in light of the evidence to conclude that he brought them from Mesopotamia (Gen 12:5) (364).

The author of Genesis includes some fascinating details about camels that one might not expect in the

Rebekah narrative (Gen 24), including observations that the camels bowed down (Gen 24:11), were unloaded (Gen 24:32), and were later ridden by the Rebecca and her servants (Gen 24:61). The author notes that Rebekah jumped down from the camel, suggesting that she did not know how to dismount (Gen 24:64; 364–65).

At least some of the references to camels in the patriarchal narratives should be taken as referring to the two-humped (Bactrian) camel which was well-known in Mesopotamia by the end of the 3rd millennium (367–68).

David had a camel herd which was tended by Obil the Ishmaelite (1 Chr 27:30). Obil is a Hebrew transliteration of an Arabic word that means camel. Apparently David hired an Arab specialist for this job (367).

Bibliographic reference:

Heide, Martin. 2011 “The Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible.” Ugarit-Forschungen 42: 331–84.

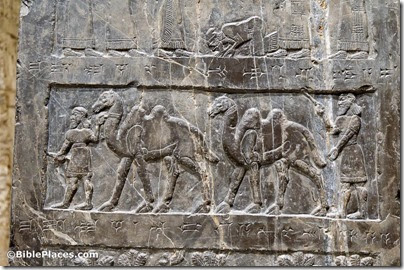

Camels carrying tribute from Musri

Depicted on Black Obelisk (ca. 825 BC), now in British Museum