(Post by A.D. Riddle)

Last December, the publisher Brill released The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna based on Collations of all Extant Tablets, by Anson Rainey.

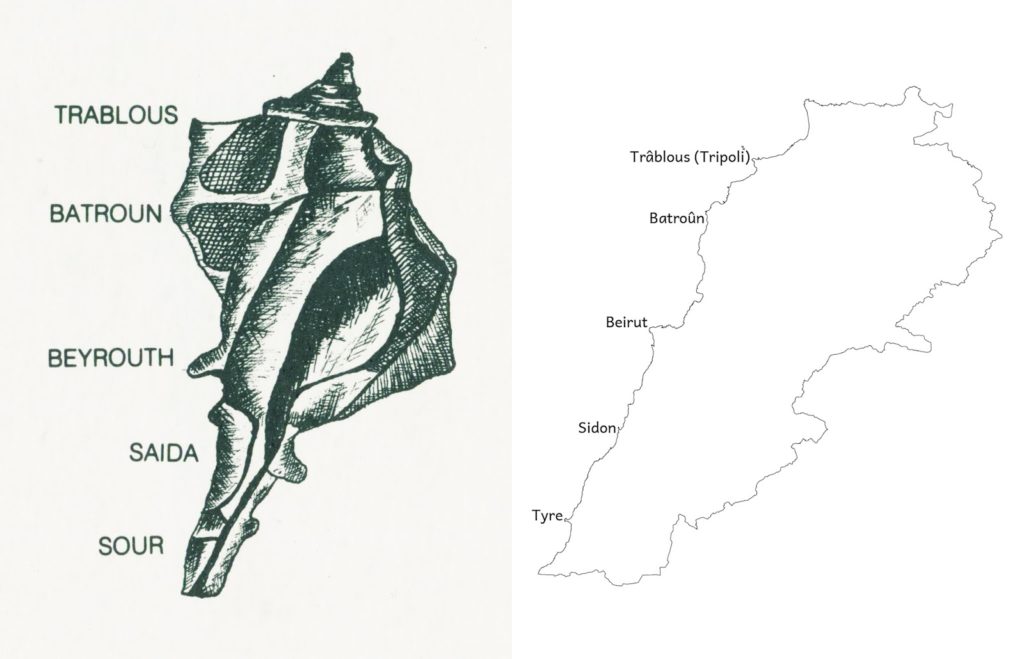

When Anson Rainey passed away in February 2011, he had not yet completed this new edition of the Amarna Letters. Rainey undertook the massive effort of producing a new collation all tablets that contain correspondence from Tell el-Amarna (the exceptions being four tablets that since their discovery were lost or destroyed; two Hittite letters, and one Hurrian letter). A collation, in this context, means a copy of the text based upon close personal inspection of the physical inscription itself. Rainey describes in the Introduction how he began work on this project as early as 1971, although the main effort commenced in 1999. Since the tablets are currently held in several museums around the globe, this was no easy task. Below are a list of the museums. The first few museums hold dozens of Amarna Letters; the rest hold far less, in most cases only two or three tablets or even just a fragment of a tablet. The Amarna Letters are housed today in:

Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

British Museum, London

The Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Louvre, Paris

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Musees Royeaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels

Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago

İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri

At the very end of last year, nearly four years after his passing, Rainey’s magnum opus was brought to completion: a two-volume set entitled The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna based on Collations of all Extant Tablets. Handbook of Oriental Studies Section 1: The Near and Middle East 110. Boston: Brill, 2015.

(This is one of a few magna opera produced by Rainey in his lifetime—The Sacred Bridge could count as one [here, review here]; his four-volume grammar of the Amarna Letters, Canaanite in the Amarna Tablets, could count as another [vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4]; an earlier publication of new Amarna Letters yet a third).

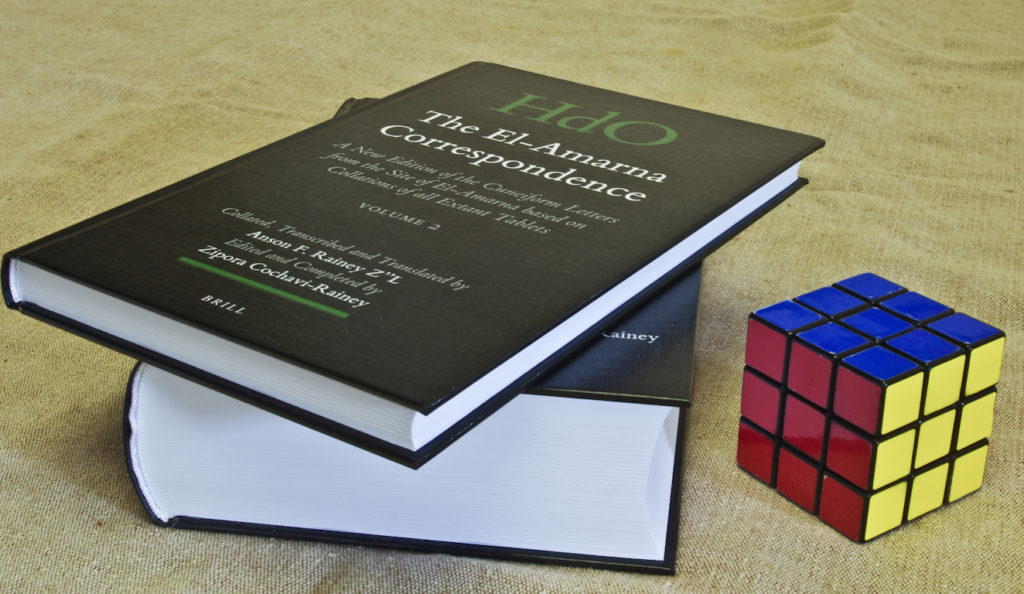

As you can see in the photo below, volume 1 is the main volume. It contains a 50-page introduction (including an essay by Jana Mynářová on the discovery of the tablets), a transliteration and English translation of every one of the nearly 350 Amarna Letters, and an Akkadian Glossary. Volume 1 is just a hair thicker than a Rubik’s Cube. Volume 2 is much slimmer and contains commentary for each letter:

- the name of the sender and recipient

- museum number of the tablet

- previous publications of the text and translations

- sometimes a brief paragraph about the disposition of the tablet or the historical situation of the tablet’s contents

- line-by-line discussion for readings of specific cuneiform signs and words based on Rainey’s collation in comparison to earlier readings.

The El-Amarna Correspondence by Anson Rainey will be the standard edition of the Amarna Letters for this generation, and anyone who uses this material in their research would benefit from consulting Rainey’s work.

As I was preparing this post, I was a little surprised by the quality of proofreading I encountered. I expected in an academic work of this type that greater care would be taken. And since they have given it a regal price tag (retail $293), I would assume the publisher could afford top proofreading talent. There were a handful of typographical mistakes in volume 1, but volume 2 contained quite a few typographical mistakes as well as factual errors. Between and within the volumes, there is confusion over EA 380-382 (their disposition, museum numbers, etc.). On another note, for volume 1, page numbers were not included on the first page of each letter, and since several letters are less than a single page in length, that means there are stretches of the volume without any page numbers at all. It would have been nice to have a page number printed on every page.