(Post by Michael J. Caba)

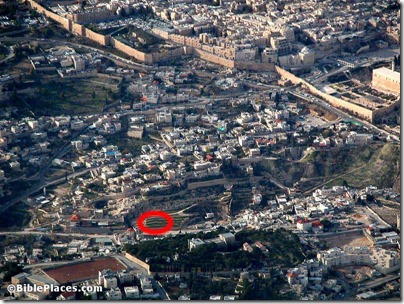

The Grotto of Saint Paul, located in the foothills on the southern side of ancient Ephesus, has recently yielded intriguing finds related to early church history. The cave has been used from the early Christian era until the late 19th century for worship purposes, but was only “rediscovered” by modern researchers in 1995.

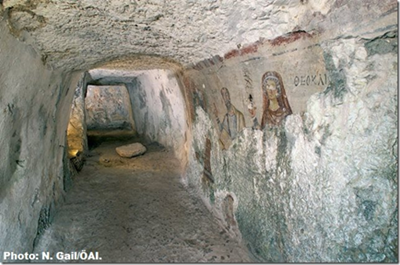

The grotto is adorned with numerous inscriptions and illustrations with the visual portrayals covering the gamut from Old Testament saints to soldiers from the Byzantine Middle Ages. The artwork itself ranges in age from the 4th century to the 12th/13th century, and the theme is consistently Christian.

The actual grotto enclosure is in the form of an elongated cavern measuring approximately 15 meters long, 2 meters wide and 2.3 meters high. The main passage leads back to a slightly expanded rectangular area measuring about 2.7 meters wide.

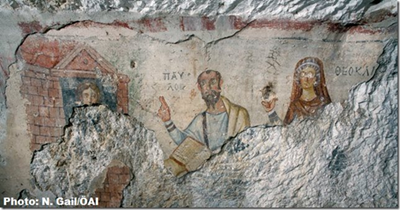

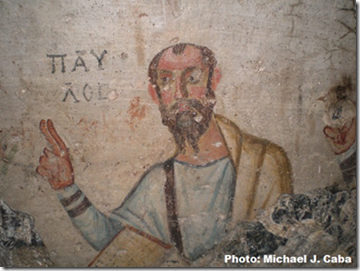

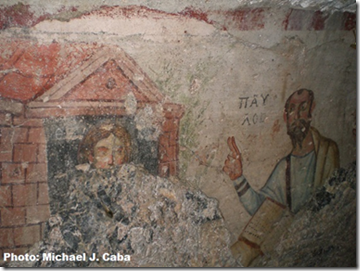

In the late 1990s Dr. Renate Pillinger from the University of Vienna discovered an early fresco on the western wall of the grotto’s passageway that includes a clear picture of the cave’s namesake, the Apostle Paul. The painting, which had been plastered over by subsequent occupants, is dated by Pillinger to the late 5th to early 6th century AD. The illustration also includes two women: Thecla to the left and her mother Theocleia to the right.

In the center of the image, Paul is shown seated with a book on his lap and his right hand raised with two extended fingers in a manner depicting a preaching gesture.

His discourse is the object of interest to the young woman Thecla, who is depicted on the left side of the fresco peering out a window.

The mural is actually a portrayal of an episode found in the apocryphal book, Acts of Paul and Thecla. Dated to the mid-2nd century AD, this text relates a story in which the betrothed Thecla listens from a window to Paul preach on “virginity and prayer.” Upon hearing Paul preach, Thecla reportedly decides to forgo her marriage and remain a lifelong God-fearing virgin, a decision for which she victoriously endures the heated opposition of friend and foe alike. Indeed, the hostility is so fierce that even her own mother (Theocleia) cries out, “Burn the wicked wretch.”

Not dissuaded from either her religion or chastity, Thecla is miraculously delivered from assorted ordeals and is reportedly even commissioned by Paul to “teach the word of God.” In this regard, Tertullian responded in De Baptismo:

But if the writings which wrongly go under Paul’s name, claim Thecla’s example as a license for women’s teaching and baptizing, let them know that, in Asia, the presbyter who composed that writing, as if he were augmenting Paul’s fame from his own store, after being convicted, and confessing that he had done it from love of Paul, was removed from his office.

The fact that Tertullian (c. 200 AD) was aware of the Acts of Paul and Thecla, and felt it necessary to comment on it, indicates both the text’s widespread circulation and its antiquity.

However, it appears that Tertullian’s denouncement of the book had little effect on the artist in Ephesus who portrayed one of its central scenes in a prominent manner in the cave.

Unfortunately, in order to protect its delicate contents, the grotto is not typically open to the public at large.

(Quotations from Acts of Paul and Thecla taken from Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 8, pages 487-492. Tertullian quote taken from Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 3, page 677.)