An Iron Age fortress next to the Yarkon River in Tel Aviv shows evidence of trade with the island of Lesbos in the 8th-7th centuries. Archaeological work done at Tel Qudadi seventy years ago have only now been published. For a large version of the image published in the article, see Leon Mauldin’s blog.

The recent storm revealed an underwater cache of weapons from the British Mandate period at Caesarea. Divers were surprised by the changes they found. “We knew things would be different after the storm, but the site was changed so much that we could hardly recognize it.”

Israel had a record-breaking number of tourists in 2010. Christians comprised 69% of all visitors.

“The most visited sites included the Western Wall (77%), the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem (73%), the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (61%), the Via Dolorosa (60%) and the Mount of Olives (55%).”

“Archaeologist” Vendyl Jones passed away recently.

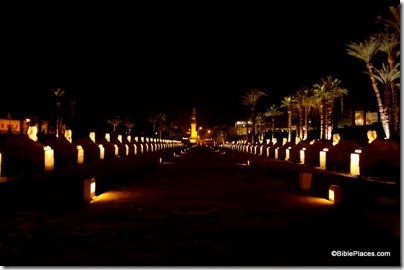

Eight Americans were killed in Egypt when their bus crashed into a parked truck. The tourists were traveling from Aswan to see the temples of Ramses II at Abu Simbel.

This editorial at the New York Times suggests one way that museums can avoid buying off the black market: excavate the archaeological sites themselves.

Geza Vermes tries to rewrite history in a lengthy article on Herod the Great, arguing in part that Herod was the victim of nasty old St. Matthew who “transformed him into a monster.” I thought it was interesting how the author preferred the passive voice when describing the deaths of the people that Herod murdered. For instance, “Augustus with a heavy heart allowed Herod to try his two sons, who were found guilty and executed by strangulation in Sebaste/Samaria.” Josephus provides the only surviving account of the episode. He writes of Herod, “He also sent his sons to Sebaste, a city not far from Cesarea, and ordered them to be there strangled” (Wars 1.551; 1.27.6).

Scholars will present papers tomorrow (Dec 30) in honor of the retirement of Prof. Amihai Mazar. Aren Maeir has posted a schedule of the meeting (Hebrew).

The annual symposium in memory of Prof. Yohanan Aharoni is planned for February 17 at Tel Aviv University. A list of the papers is given here. Part II is entitled, “Debating the Future of Biblical Archaeology: Do Science and Technology Show the Way?”

If you need your football fix while in Israel, the full-contact amateur Israel Football League may beat staying up until dawn.

If you ever drive to the nature reserve at En Gedi, you may want to avoid parking under the trees next time.

HT: Joe Lauer, Keith Keyser, Gordon Govier