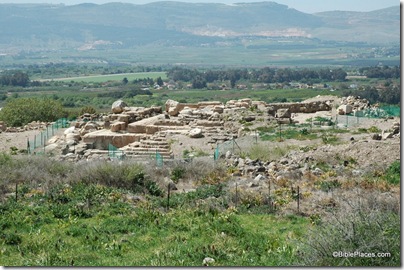

Conservation work on the beautiful 4th century Lod mosaic has revealed a number of sandal prints.

From the Jerusalem Post:

“We look for drawings and sketches that the artists made in the plaster and marked where each of the tesserae will be placed,” Neguer said. “This is also what happened with the Lod mosaic: beneath a piece on which vine leaves are depicted, we discovered that the mosaic’s builders incised lines that indicate where the tesserae should be set, and afterwards, while cleaning the layer, we found the imprints of feet and sandals: sizes 34, 37, 42 and 44.”

He said that similarities of the footprints of the sandals lie in the fact that sandals today are based on the footwear of the past.

“They’re simple,” Neguer said. “If it’s comfortable, why change it.”

The 1,700 year old mosaic, which is one of the largest in Israel, was discovered in the city of Lod in 1996 and was covered again when funding could not be found for conservation.

The full story and photographs are here (see also Arutz-7). The Israel Antiquities Authority has four high-resolution photos for download (press release here; zip file here). This mosaic was mentioned previously on this blog here. These footprints are not related to another set of “footprints” discovered in April.