(Post by A.D. Riddle)

Several years ago, Chris McKinny wrote a series of posts named “Secret Places.” We resurrect it now to draw your attention to another little-known museum in Jerusalem.

If you have been to Israel a few times, and names like Edward Robinson or Charles Warren are starting to mean something to you, then you may want to add this museum to your next visit.

The museum is located within the compound of Augusta Victoria church/hospital on top of the Mount of Olives. The church’s bell tower is a prominent landmark that can be seen at some distance from several directions. You have certainly seen it, even if you were not aware of what it was.

The German Protestant Institute of Archaeology in the Holy Land occupies a house located right behind (east of) the church. As you walk in from the main gate and follow the road to the right, you will see green signs in front of the church that direct you towards the “German Institute of Archaeology.”

The museum is located in the lower story of this house. It highlights the work of Conrad Schick, Gottlieb Schumacher, and especially Gustaf Dalman. On display you will find large models of Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher constructed by Schick, survey instruments used by Schumacher to draw maps and plans, as well as signs with biographical details.

Wood and cardboard model by Conrad Schick, 1867.

Most of the museum, however, is dedicated to the work of Gustaf Dalman. Dalman was the first director of the Institute. His name may be familiar to some readers as the author of Sacred Sites and Ways: Studies in the Topography of the Gospels (1935), one of the few works by Dalman translated into English. He was an expert in the study of, well, pretty much anything related to the Holy Land.

“Dalman’s main aim and starting point was to shed light on the biblical and post-biblical past of Palestine. Instead of only studying texts and relics of the past, and the Bible, he studied the daily activities and customs of the Arab population of Palestine…he combined anthropology, comparative religion, music, and biblical schalarship with geography, geology, botany, astrology, meteorology and zoology into a…new multi-disciplinary field of study…Palestinology”

(Abdulhadi-Sukhtian 2013: vii–viii).

Dalman recorded and collected just about anything you can imagine, and many of these collections are represented in the museum: photographic slides, ancient pottery and coins, herbs, rocks, and limestone models of tombs, presses and Palestinian houses. The models have removable roofs and walls so you can see the interior layout of the structures. It is a little mind-boggling that one man produced all this work.

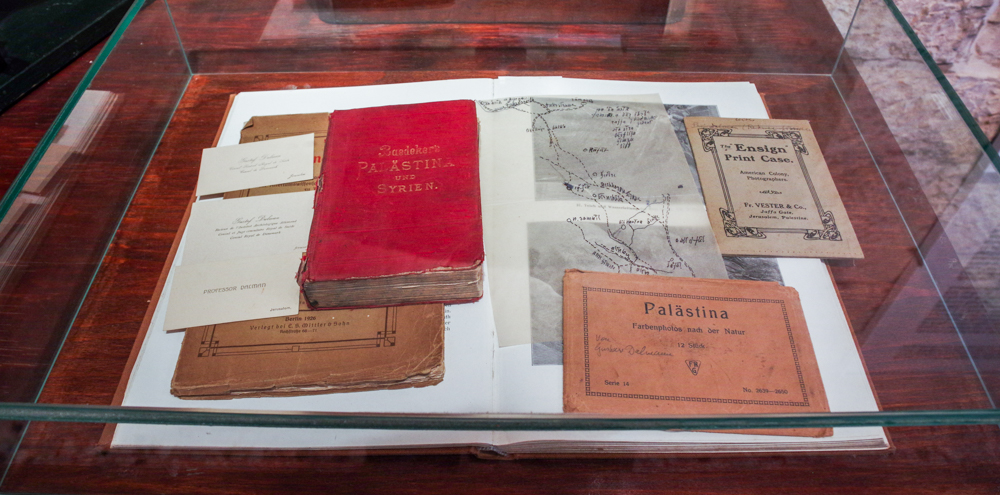

Theologians and pastors would come to the Institute for a three-month course taught by Dalman. A map in the museum shows his itinerary for field trips and a display case contains Dalman’s personal copy of Baedeker Palestine and Syria guidebook.

The museum is not large. You are free to visit, but the Institute requests that you call or email beforehand if you have a group. I would recommend keeping groups very small—ten people would start to feel crowded. A visit will only take about an hour, and most of the labels and signs provide English translations. While you are in the Augusta Victoria compound, the church has a collection of inscribed ossuaries in one of the side rooms. Some of the ossuaries have names like Matthew, Jesus, and Mary. The church also has a life-size replica of the ark of the covenant, and the Bibles of Kaiser Wilhelm II and Empress Augusta Victoria. From the top of the bell tower, on a not-particularly clear day, I was able to make out Baal Hazor, Nebi Samwil, the Dead Sea, and Herodium. It provides a nice view of Jerusalem’s Old City as well.

Contact information for the German Protestant Institute can be found on their website.

Citation

Abdulhadi-Sukhtian, Nadia, trans.

2013 Work and Customs in Palestine, Vol. 1: The Course of the Year and the Course of the Day. 2 parts. Ramallah: Dar Al Nasher.