At the annual meeting of the Near East Archaeological Society last November, Dan Warner gave an update on the excavation of the Gezer water system. The tunnel seems to date to the Middle Bronze Age: the pottery from the tunnel is Late Bronze and Middle Bronze, and the tunnel’s position vis-à-vis the Canaanite Tower indicates a relationship between the two. The tunnel possesses a number of interesting features which raise questions about its function—was it in fact a water system, or was it something else?

The tunnel descends 150 feet below the surface and has a barrel-shaped ceiling and stairs. There are two carved arches some distance apart, sort of like ribs, that have no real architectural purpose and appear to be ornamental. One of the rib-arches can be seen in the photo below. There are also niches carved into the walls of the upper part of the tunnel, some of them decorated with arches or recessed frames, and one of them with a betyl. Some of the niches can also be seen in the photo below.

Dan Warner’s team has now cleared 80 feet beyond the earlier excavation of Macalister. At the base of the tunnel, there is a basin and beyond that a man-made cavern which extends east. According the geologists, the aquifer is 30 meters beneath the cavern, so this is not obviously a water system. If it is a water system, why did they carve niches and arches and a cavern? And why is it so large? Could the tunnel have instead had a different function?

I was struck by some similarities to a cultic tunnel at Arsameia on the Nymphaios River, near the more famous site of Nemrut Dağ in Turkey. Dan Warner did make mention of the cultic use of caves in the Greek world (both in literature and archaeology), so I proceed to note the similarities here even though there is really no apparent geographical or chronological connection between Gezer and Arsameia. Arsameia-on-Nymphaios is a cultic center which occupies the highest elevation in the photo below.

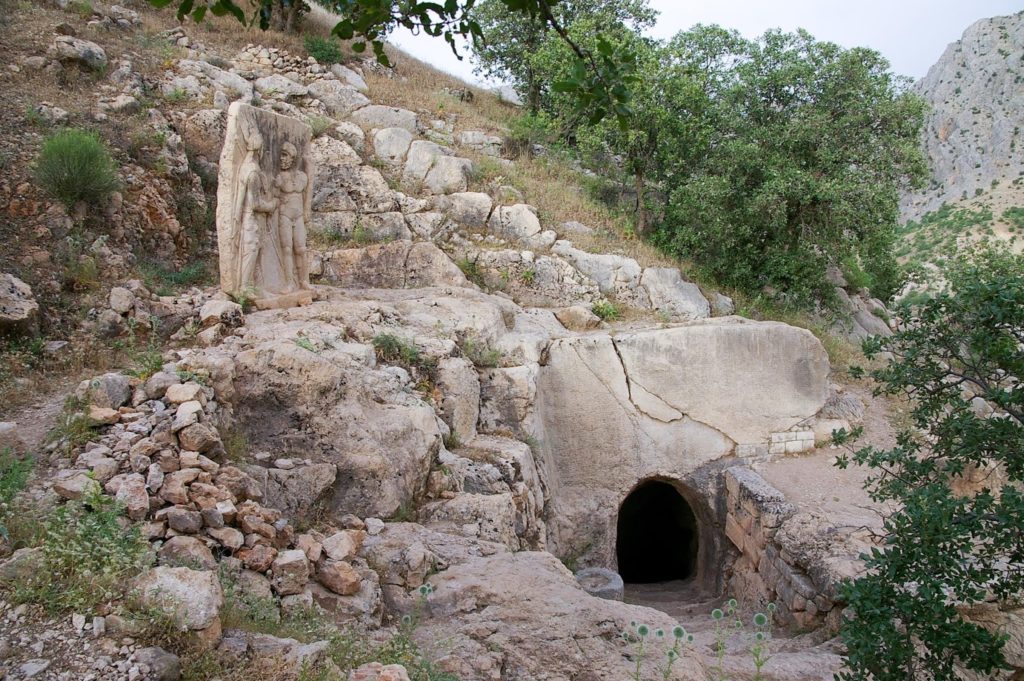

At the site, there is a Great Rock Chamber carved into the mountain, various stelae, and a monumental staircase. But there is also a tunnel which descends diagonally into the mountain. Above the tunnel there is a relief of Heracles (Hercules) and Antiochus I Theos, king of Commagene, and the longest Greek inscription in all of Anatolia. Like Gezer, the tunnel has stairs and a barrel-shaped ceiling. The tunnel is 520 feet long and terminates in a small cavity with no indication of its function.

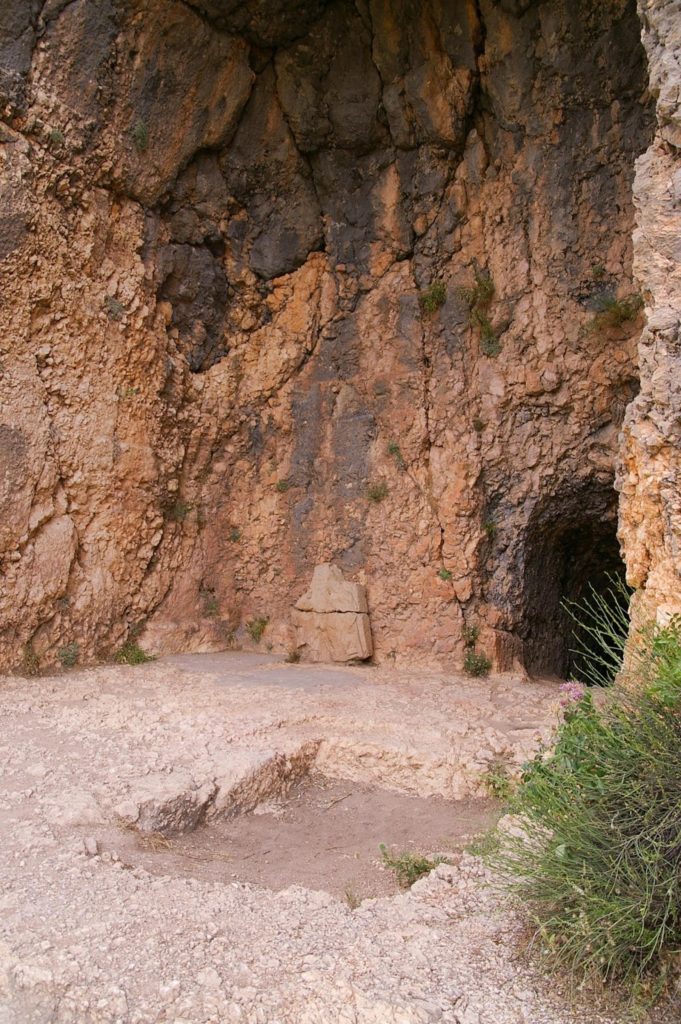

Arsameia-on-Nymphaios tunnel entrance with inscription and stairs (also from PLBL vol. 9).

The tunnel at Arsameia-on-Nymphaios is described in Brijder’s new book. He calls it “a mysterious, dark and incredibly long tunnel in rock.”

After such enormous labour and effort it was disappointing that the very long, deep and dark tunnel had not yielded any evidence as to its function. It is clear that it did not lead to a subterranean spring. The suggestion of a water tunnel does not seem to be very convincing either, although it cannot be excluded. Dörner notes: ‘The tremendous effort that went into digging this rock tunnel of Arsameia could only have served a very special purpose, and since the tunnel is situated at a particularly central spot in the cultic area of the hierothesion, the thought of a cultic function of the tunnel simply occurred to me’ (figs. 161–162). According to him, the making of a rock tunnel was not defined by practical intentions, but by religious ones. ‘It seems rather logical to assign the large rock tunnel in Arsameia to the cult sphere of the god Mithras, who is the “God born from the rock.”’ (Brijder 2014: 255)

As a side note, the Great Rock Chamber/Hall also has a tunnel with barrel-shaped ceiling and stairs. The tunnel is not nearly as long—only 33 feet. The tunnel leads to a small platform which overlooks a square, 20-foot-deep chamber without any doors or stairs. Again, the function of the tunnel and chamber are unclear, but Brijder inquires whether this could have been intended as a burial chamber and later converted to a cenotaph.

It will be interesting to see what new developments come from Gezer this summer, and if Dan Warner can come closer to determining the tunnel’s function. An article about last year’s work on Gezer tunnel can be read here, and the excavation website is here.

Brijder, Herman A. G., ed.

2014 Nemrud Dağı: Recent Archaeological Research and Conservation Activities in the Tomb Sanctuary of Mount Nemrud. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.