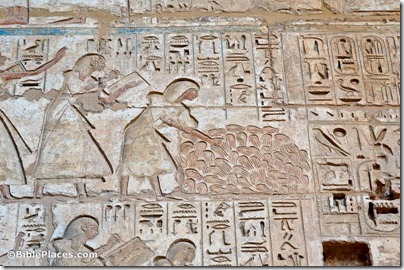

The results of the first season of the Jezreel Expedition are summarized at The Bible and Interpretation. The regional survey this summer was successful in preparing the team for beginning excavations next year. The article begins:

Members of the Jezreel Expedition headed by co-directors Norma Franklin (Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa) and Jennie Ebeling (Department of Archaeology and Art History, University of Evansville) conducted an intensive landscape survey of “greater Jezreel” in June 2012. The main goal of the inaugural season was to record surface features in a three square kilometer area to the west, north, and east of Tel Jezreel in order to identify areas for excavation in summer 2013 (Figure 1). The Jezreel team documented more than 360 features, including cisterns, cave tombs, rock-cut tombs, agricultural and industrial installations, terrace and village walls, quarries and more; most of these features had never been systematically recorded before. The results of this survey shed light on the extent of different settlements at Jezreel from late prehistory through to the 20th century CE Palestinian village of Zer’in.

The article also includes an image from the recent LiDAR scan. The city of Jezreel is best known as the location of Naboth’s vineyard and Jehu’s coup. Here Jehu ordered the deaths of the kings of Israel and Judah as well as Queen Jezebel (2 Kings 9-10). In a 2008 article, co-director Franklin argued that the fortified enclosure of Jezreel was constructed not by Ahab but nearly a century later by Jeroboam II.  Tel Jezreel and Mount Gilboa from the west (photo from the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands, volume 2)

Tel Jezreel and Mount Gilboa from the west (photo from the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands, volume 2)