(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

Jesus began one his parables by saying, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him and departed, leaving him half dead.” (Luke 10:30, ESV.) Thus began the well-known “Parable of the Good Samaritan.” Although that particular route would have been well-known to Jesus’ hearers, most readers of the Bible today are not familiar with it.

Enter the Pictorial Library of the Bible Lands … One of the most admirable features of the PLBL is that it takes you to out-of-the-way places that you have never visited but always wished that you had.

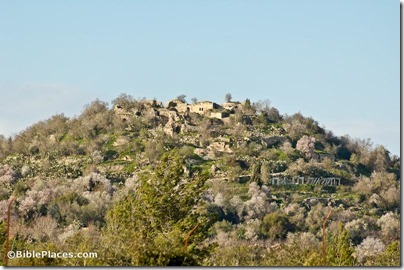

Our picture of the week is from Volume 4 of the PLBL and shows us the remains of the Roman road that led from Jerusalem to Jericho in Jesus’ day. Elsewhere in the Bible, this route is referred to as the Ascent of Adummim (Josh. 15:7; 18:17).

In the picture, the viewer is looking east toward the rugged hills of the Judean Wilderness that lie between Jerusalem and Jericho. In the foreground the remains of the road can be seen stretching out before the feet of the photographer. The small cliff to the right seems to be man-made and was probably cut to give more space for the road. Only the foundation of the road remains today.

The PowerPoint notes from the PLBL provide the following insights into this significant road (the links have been added to the notes for the benefit of our readers):

The “Ascent of Adummim” was the main route from Jericho to Jerusalem in antiquity. It followed a ridge located south of the Wadi Qilt and north of Nahal Og, and near Jerusalem was forced to cross the Nahal Og at a more passable location. Among the biblical events which likely occurred on this route were David’s flight from Absalom (2 Sam 15-16), Zedekiah’s flight from the Babylonians (2 Kgs 25:4), the story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37), and Jesus’ travels from Jericho to Jerusalem (e.g., Luke 19:28).

How long does it take to walk from Jericho to Jerusalem? On one recent occasion, it took a group of hikers 8 hours to cover the distance of 15 miles (24 km), with an elevation gain of about 3,400 feet (1,060 m). Not counting breaks, we walked for six and a half hours. Had it been hotter or had we run into any difficulties, the journey would have taken longer.

Jesus traveled this route many times. He likely came this way most of the times that he journeyed to Jerusalem from Galilee, though we know of at least two occasions when he attempted to travel through Samaria (John 4; Luke 9:52-53). Scripture records at least two trips by way of Jericho, but he probably went this way dozens of times in his life. It’s a reasonable conclusion that Jesus’ parents had to climb back up this route to Jerusalem after realizing that their twelve-year-old son was not in their caravan (Luke 2:41-50). Parts of the Roman road are still visible in places, and the way today is safe and pleasant.

This picture and over 1,500 others are available in Volume 4 of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands and is available here for $39 (with free shipping). More photos and information about this region are available on the BiblePlaces website here. For further discussion and images that illustrate the story of the Good Samaritan, see this page on LifeintheHolyLand.com.