(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

Someone who has been to the Western Wall today and has seen the big, beautiful plaza that spreads out before the wall may be surprised to learn that for much of the past few centuries, the Jews worshiped at the wall in a much smaller space. What’s more, for about 20 years in the middle of the last century, they couldn’t worship there at all.

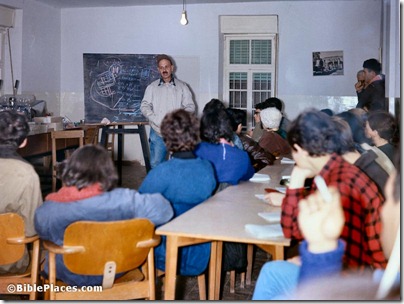

Our picture of the week comes from a collection called Photographs of Charles Lee Feinberg, which is available for purchase at LifeintheHolyLand.com. Dr. Feinberg was a Bible professor who took several trips to the Middle East between 1959 to 1968. His collection is a rare jewel of color photographs from a period when the region was less densely populated and developed.

Pictures from the 1800s and photographs like the one below from the mid-1900s show that the old “Western Wall Plaza” wasn’t much of a plaza. It was more like a hallway … or maybe just a closet.

However, it was still revered by the Jewish people because it was the closest they could come to the place where the temple once stood, and the wall itself was part of the temple complex during the first century A.D. (It was and still is part of a retaining wall that holds up part of the Temple Mount.)

During Israel’s War of Independence in 1948, the Jews lost control of the Old City of Jerusalem and with it lost access to their most revered place of worship: the Wailing Wall … or as they call it these days, the Western Wall. (When I was in college, one of my Jewish-born professors said that they didn’t call it the Wailing Wall anymore because they had done enough wailing.) So from 1948 until the Six Day War in 1967, the Jews were not allowed to worship at their most holy site.

All that changed in 1967 when Israeli soldiers defeated the Jordanian forces and captured the Old City. In his book, The Battle for Jerusalem, Lt. Gen. Mordechai Gur captures the emotions of that fateful day as he and his men visited the Western Wall for the first time in over 20 years:

We came to the narrow little gate, known as the Mograbi, and lowered our heads to duck through it to the top of the gloomy, crooked, steep, narrow stairs. We heard the sounds of praying as we went down the steps. The space in front of the wall was packed with people. Soldiers were praying, some swaying devoutly as if in synagogue, although they were still wearing their stained battle dress.

To our right and above us was the wall: huge blocks, gray, bare, silent. Only shrubs of hyssop in the cracks, like eyes, gave the stones life. We saw that somebody had set up an Ark, brought from a military synagogue, and that in front of it stood Rabbi Goren praying in a hoarse voice. he had been praying non-stop now for two hours.

The site, the prayers, the great victory, the thoughts of the fallen seemed to release the paratroopers from their armor of iron and many of them wept unashamedly, like children. …

I drew near the crowd of soldiers praying, and when they noticed me they indicated I should go to the front. I thanked them but stayed at the back.

Despite the great congregation, I had to undergo my own private experience. I did not listen to the prayers, but raised my eyes to the stones and looked at the paratroopers praying, some with helmets on their heads and some with skullcaps. I scanned the buildings closing in on us from three directions, which gave the square a very intimate character.

I remembered our family visits at the wall. Twenty-five years ago, as a child, I had walked through the narrow alleys and markets. The impression made on me by the praying at the wall never left me. My memories blended in with the pictures that I had seen at a later age of Jews, with long white beards, wearing frock coats and black hats. They and the wall were one.

Shortly after this, the modern, spacious Western Wall plaza was created.

Excerpt from Mordechai Gur, The Battle for Jerusalem, trans. by Philip Gillon (New York: Popular Library, 1978), pp. 376, 378.

This picture and over 400 others are included in a collection called Photographs of Charles Lee Feinberg, and can be purchased here for $20 (with free shipping). Additional images of the Western Wall throughout the last two centuries can be found here, here, and here.