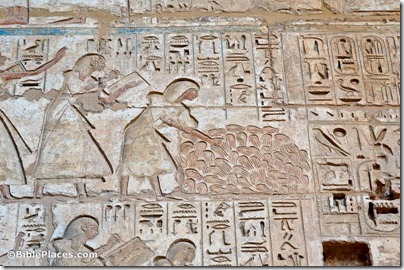

Archaeologists have found a collection of right hands at the Hyksos capital of Avaris in Egypt. Collecting body parts was one ancient way of counting victims (cf. 1 Sam 18:25). Israeli scientists have developed a way to predict the location of sinkholes near the Dead Sea. Clay rods from the Neolithic period found years ago are not phallic symbols but were ancient matches for starting fires. A summary of the 13th season at Hippos/Susita has been released by the University of Haifa. There are more photos here. A large olive press from the 6th-8th centuries AD has been discovered in Hod HaSharon on Israel’s coastal plain. The National Project to Document Egypt’s Heritage has begun with the tombs of Beni Hasan. The Aleppo citadel has allegedly been damaged by shelling by the Syrian army. Eilat Mazar will be excavating more of the area between the Temple Mount and the City of David later this month. Nir Hasson has more on Sir Flinders Petrie, the archaeologist who lost his head. Wayne Stiles takes a closer look at Nebi Samwil and the neighboring Gibeon and concludes that they reveal similar spiritual lessons. Gordon Franz has obtained a copy of pseudo-archaeologist Robert Cornuke’s doctoral dissertation and finds that it’s a sham. Paul V. M. Flesher writes about the latest finds in the Galilean town of Huqoq. Leon Mauldin shares a photo of Mount Ararat with a rainbow. Haaretz has some tips for finding wifi in Israel. HT: Joseph Lauer, Jack Sasson  A pile of hands used for counting the dead, depicted at mortuary temple of Ramses III in Medinet Habu (photo source)

A pile of hands used for counting the dead, depicted at mortuary temple of Ramses III in Medinet Habu (photo source)

Nir Hasson of Haaretz reports on the study of ancient plants at the Philistine city of Gath.

Until a few years ago most archaeologists would not even have considered these to be archaeological finds. The focus on them could symbolize the new road the discipline has taken in general, and Israeli archaeology in particular. Known as microarchaeology, this new field use precise scientific instruments to interpret more elements of the ancient record, making it more complex and at times, more human. Instead of great kings vanquishing cities, pillaging, murdering and being murdered, it also tells the story of cultural transformation and of simple urban dwellers. Called phytoliths, the white spots are what remains after most of a plant has decayed, as a kind of skeleton made of minerals. [Yotam] Asher is doing his Ph.D. on what phytoliths can teach us. Those at Tel Tzafit are what is left of plants that lived 3,300 years ago. A preliminary look under the microscope shows that one spot is what remains from a pile of domesticated wheat while another is of unidentified wild plants. "It’s possible that in one place was a sack of hay and in another, a sack of wild plants, or that these are plants that were on a roof that collapsed," Asher says.

The full story is here. The head archaeologist of the Gath project calls the article “great.” Joseph Lauer observes that the “four-horned altar” mentioned only had two horns.

- Tagged Excavations, Philistines, Technology

With the discovery of a LMLK seal at Azekah, Omer Sergi of Tel Aviv University gave an impromptu lecture about LMLK seals. Daily updates by volunteers are posted here.

“Archaeological sites that currently take years to map will be completed in minutes if tests underway in Peru of a new system being developed at Vanderbilt University go well.”

Egyptian officials are trying to bring back tourists by opening new tombs, including the tomb of Meresankh.

An Israeli journalist has filmed a mass grave near the Golden Gate that he suggests dates to the Roman destruction of Jerusalem.

Like the tower of Pisa, the Colosseum of Rome is leaning.

James Mellaart, excavator of Çatalhüyük, passed away this week.

More than a hundred people gathered at the tomb of Sir Flinders Petrie this week to celebrate the 70th anniversary of his death.

The latest in the wider world of archaeology is reviewed by the ASOR Blog.

Congratulations to Geoff C. and Frank P., winners of Walking in the Dust of Rabbi Jesus.

HT: Jack Sasson, Wayne Stiles, Joseph Lauer

- Tagged Discoveries, Excavations, Giveaway, Italy, Jerusalem, Shephelah, Turkey, Weekend Roundup

The on-going excavations of Megiddo are the subject of a report by Nir Hasson in Haaretz. The story focuses on the 10th-century debate but mentions a similar text-archaeology problem in the 15th century.

Archaeologist Israel Finkelstein is leading his sweating guests to a corner of Tel Megiddo. He points to a black stain on a rock, which on closer inspection turn out to be charred seeds. “This,” he says, “is the most important find at Tel Megiddo.”

[…]

In one of the four excavation areas on the mound, each marked by its own flag, we come back to the charred crumbs Finkelstein says were the mound’s most important find. Here, under a rainbow flag, we are told they are tiny seeds that Megiddo’s inhabitants collected around 3,000 years ago. They went up in flames when the city was destroyed.

They are important because of their location in relation to finds above and below them. Organic material like this is especially valuable because it can undergo carbon-14 testing, allowing the level where it was found to be dated.

[…]

One of the black layers indicates destruction in the 10th century. Finkelstein’s detractors say David destroyed this city – an idea that Finkelstein rejects because he says the carbon-14 dating rules out the possibility that the city was destroyed suddenly. It shows a gradual process.

The difficulties in reconciling text and archaeology are not limited to the Bible. Those who have great confidence in archaeology and their interpretation of the material remains tend to denigrate textual accounts.

Not far away, under a Jolly Roger, a group is excavating fortifications. Here, the finds also defy an ancient text. But this time it’s not the Bible, it’s the Egyptian record of the conquest of Megiddo by Pharaoh Thutmoses III in the 15th century BCE, describing a seven-month siege.

But the excavators discovered that the city walls at that time were meager. Finkelstein explains the discrepancy as he does with the Bible. The Thutmoses text was written to glorify the pharaoh’s vanquishing of a supposedly mighty city.

This proposal is less satisfying when considered more carefully. According to Thutmoses’ own records, his army surprised the Canaanite forces when they traveled through the Megiddo pass (Nahal Iron). With the Canaanite soldiers positioned near Jokneam and Taanach, Megiddo was an easy target. Yet the Egyptian soldiers pursued plunder and the Canaanites were able to escape into the safety of the city walls. A seven-month siege was required to take what could have been easily captured with some basic army discipline. While Thutmoses III certainly was glorified by his ultimate defeat of the Canaanite coalition, it is not easy to understand why he would have invented such an embarrassing story.

The full story is here. The Hebrew version includes a slideshow with 6 photos of the excavations.

Some day I’ll explain why many scholars reject Finkelstein’s dating of 10th-century remains at Megiddo.

HT: Joseph Lauer

- Tagged 10th Century, Excavations, Jezreel Valley

Archaeologists at Hazor have discovered 14 large storejars full of grain burned in a massive conflagration during the period of the judges (c. 1300 BC). Volunteer Rob Heaton shares his experiences in the last days of the dig and more.

The 2012 Lautenschläger Azekah Archaeological Expeditions Blog is being updated daily. Yesterday they confirmed the discovery of ancient fortifications.

Matti Friedman describes a day of digging at the Philistine city of Gath.

The Israel Antiquities Authority’s Archaeological-Educational Center invites the public to

“Archaeologists for a Day” program at Adullam Park in the Shephelah on Monday, July 30. The cost is 20 NIS and pre-registration is required at [email protected], Tel: 02-9921136, Fax: 02-9925056. The invitation (Word doc in Hebrew) provides more details.

Seth Rodriquez has identified the most interesting photos for a Bible teacher from NASA’s Visible Earth website.

High-tech aerial photos remove the ground cover so you can see what lies below.

In a new article at The Bible and Interpretation, Yosef Garfinkel reviews some attacks on his work at Khirbet Qeiyafa and provides “an unsensational archaeological and historical interpretation” in which he provides 14 “facts,” concluding that “the site marks the beginning of a new era: the establishment of the biblical Kingdom of Judah.” That last word is problematic.

At Christianity Today, Gordon Govier interviews evangelical scholars about the potential impact of the discoveries at Khirbet Qeiyafa.

A 19th-century map of Jerusalem has been discovered in an archive in Berlin.

The story about Islamic clerics wanting to destroy the Egyptian pyramids is not true.

HT: Roi Brit, Joseph Lauer, Jack Sasson

- Tagged Egypt, Excavations, Galilee, Jerusalem, Shephelah, Weekend Roundup

Paul Lapp’s description of his April-May 1967 excavations at Tell er-Rumeith (Ramoth Gilead?) provide some interesting insights into the life of an archaeologist nearly 50 years ago. The account continues from yesterday’s post:

“The first few hours on the mound were chilly and windy, but by the time of the coffee break at 9:45, the sun had warmed the tell to a comfortable degree. The fifteen minute respite sustained us until noon when work stopped for 45 minutes. After lunch we excavated for three more hours till 4 o’clock when the laborers began to return to Ramtha and we fortified ourselves with tea and bread. Invariably most of the field supervisors then returned to their plots to draw the top plans or help one another with section drawings. Darkness would force us to leave the mound and return to our camp by six o’clock. It was then almost time for supper. After a half hour elapsed in the mess tent we were ready to begin the pottery reading. We had worked out a system so each knew when he was due at the pottery tent, and in that way there was no delay. The remainder of the evening was given to preparation of the field books. Pressure lamps are not conducive to the kind of precision that is required for keeping records so one has to be careful to double-check each entry. The field book up to date, it was then almost eleven o’clock and time to retire for the night. From that moment on no human sound broke the stillness of the night in the plains of Gilead. Every minute of sleep counted in order to be ready to face the rigors of the next day’s work.

(photo source)

“Our camp consisted of about a dozen tents, mostly of the small variety, and was located to the east at the base of the mound, which is largely a rocky outcrop. With the exception of several chilly nights at the beginning of the season and a strong wind which cost us a half-day’s work, the weather was nearly perfect. The countryside was green when we began and golden when we finished—just in time, for we were beginning to lose our workers to the grain harvest. Despite our pre-Easter apprehensions over the severe winter rains, it proved to be an ideal time for the campaign. In the end we felt we had a complete enough story of the tell to abandon the site to some future excavator, and we were determined to set down the story as soon as possible. However, the unforeseen event of June has delayed this report.

“My last diary notation on the Rumeith dig reads, ‘The end of a phase or an era.’ This was written on May 12, 1967; the first entry dates back to the sounding of the spring of 1962. I was thinking of the loss of Aboud, who had always been my right hand man at excavations, of the talk of major changes for the Jerusalem School [of ASOR], of the fact that this was the last campaign of a small scale that I would conduct as part of the School’s annual program. At the time, however, I was not thinking of the Six Day War, though the final words of my diary were fulfilled like an ancient prophecy. This accounts for the disjointedness of this letter, begun in Amman during the war, continued in Tehran and Athens, and finally finished in Jerusalem. Incidentally let me take this opportunity to thank all our ASOR friends for their kind expressions of concern during the crisis, to give assurance that the Lapp family is safely and happily back home in Shafat, and to express the hope that some of you will have the opportunity to visit us during the coming year.”

Travel from east Jerusalem to Tell er-Rumeith on the heights of Gilead was not difficult in April and May 1967 as there was no international border to cross. As he observes, everything was to change the next month.

Paul Lapp died tragically in a swimming accident in Cyprus a few years later. His wife, Nancy Lapp, edited these essays and prepared it for publication while raising their five young children.

The Tale of the Tell is still available both new and used from the publisher and Amazon and may be available in your local library as well.

- Tagged Excavations

The BiblePlaces Blog provides updates and analysis of the latest in biblical archaeology, history, and geography. Unless otherwise noted, the posts are written by Todd Bolen, PhD, Professor of Biblical Studies at The Master’s University.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. In any case, we will provide honest advice.