Last week Eilat Mazar announced the discovery of a massive wall in Jerusalem dating from the time of Solomon. Unfortunately, the information was communicated on location in a press conference, and it has been difficult to figure out what exactly she said. It seems that ambiguity served her well, for it apparently disguised some important details, such as the fact that most of what she announced she had previously excavated, announced, and published in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Whatever she discovered in the brief excavation of 2010 either was not announced, not reported, or identical to what she has previously reported.

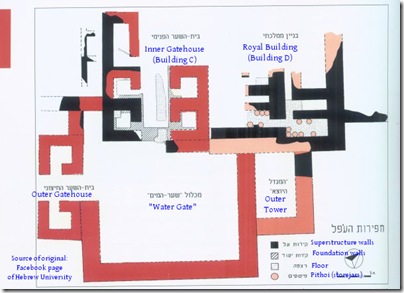

There are other problems. One concerns the definition of terms. What you think of as a “wall” is what Mazar calls the exterior of two buildings, one of which she (but few others) believes is a gate.

Perhaps these buildings served as the defensive line of the city. Perhaps she found a new section in 2010 that is a city wall. But if you’re thinking she found a wall line like at Megiddo, Lachish, Hazor, Dan, or other places in Jerusalem, then you’re mistaken.

Another problem is that her previous publications give the sense that she is changing her interpretation to fit a more biblical narrative and date without new data to support this conclusion.

My friend Danny Frese has compared her publications of the site and we think they suggest that her analysis of the data owes more to what she would like to find than what she has found.

Concerning Building C, “The Gatehouse,” she wrote in 1980s about a fill under the floor of the south chamber. The fill held about 50% EB and MB sherds; the latest pottery found in the fill was “from the Iron II” (1987: 62). More specifically:

There was also a small quantity of wheel-burnished sherds [in the fill] which indicate a date sometime in the ninth-seventh centuries B.C.E. (ibid.).

She notes two particular sherds from the fill that are from distinctive bowls which appear in the 10th and 9th centuries (1989: 20).

The ceramic data as presented above do not enable precise determination of the time of construction [of the gatehouse], which must be cautiously defined as between the 9th and 7th centuries B.C.E. (1989: 20).

Unfortunately the finds in the locus [in the south chamber] are extremely scanty and do not permit a more accurate dating than between the 9th and 7th centuries (1989: 59).

But in 2006, she wrote concerning the two sherds from distinctive bowls mentioned above:

Bowls of this type have been studied extensively and date mainly to the 10th century, continuing into the 9th century BCE. The ceramic data were insufficient to provide a more precise determination within the terminus post quem [earliest] time frame for the construction of Building C (2006: 783-84).

In other words, the evidence for dating the gate to the 10th century are two sherds that were also in use in the 9th century.

Concerning Building D, “The Royal Building,” she wrote in 1989 about the dating of the lower floor, beneath which was:

an intact black juglet of the type characteristic of the 10th and 9th centuries B.C.E. The juglet was found hidden between stones of one of the foundation walls of the room, as if it had been placed there intentionally by the builders as a sort of private foundation deposit. On the basis of the pottery finds, including the juglet, the time of the laying of the lower floor, and hence also of the entire building, can be determined as the 9th-early 8th centuries B.C.E. (1989: 60).

But in 2006, with no additional excavations having occurred since 1989, she wrote about the black juglet:

It was found hidden, as though placed there intentionally by the builders as a construction offering of sorts. The juglet appears to be characteristic of the 10th century BCE; there are clear differences between this early type of juglet and its later 8th-century form, examples of which were also found in the excavations on the eastern slope of the Western Hill. Unless further research conducted on the typology of black juglets indicates otherwise, it seems clear that the early type with the straight neck, ovoid body, and button base, like the example found in the Ophel, is characteristic first and foremost of the 10th century BCE (2006: 784).

The question we ask: what changed? Distinguishing between pottery of the 10th and 9th centuries has not been clarified in the intervening years. If anything, the debate has only intensified. Yet Mazar concludes in her 2006 article:

A new understanding of the finds from the excavations of the monumental fortification line in the Ophel has enabled its dating to as early as the 10th century BCE (2006: 75).

The “new understanding” was a reinterpretation of a juglet to an earlier date without any supporting evidence. That allows the entire “gate complex” to be dated to the 10th century. And suddenly you can publish an article entitled “The Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem.”

Given her press conference announcement, we presume that she found new material in her 2010 excavations that confirm her earlier conclusions. Her case would be more compelling, however, if it didn’t appear that she had a pre-determined outcome.

Sources Cited:

Mazar, Eilat. “Ophel Excavations, Jerusalem, 1986.” Israel Exploration Journal 37.1 (1987) 60-63.

Mazar, Eilat and Benjamin Mazar, Excavations in the South of the Temple Mount: The Ophel of Biblical Jerusalem. Qedem 29. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1989.

Mazar, Eilat. “The Solomonic Wall in Jerusalem.” Pp. 775-86 in “I Will Speak the Riddles of Ancient Times”: Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honor of Amihai Mazar on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Edited by A. Maeir and P. de Miroschedji. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006.