I have more to say about Khirbet Qeiyafa, but time is tight right now and a more careful presentation will have to wait. But there are a few developments I can note and a few comments I can respond to, all in brief fashion.

First, G. M. Grena posted on the comments here this morning that the PowerPoint presentation that excavator Y. Garfinkel gave at the ASOR meeting last week is now available in pdf format. This is a great resource for those who want to know more but couldn’t be there.

Second, if you’re interested in following the ostracon on its tour of the most expensive cameras in the world, you can do that here. Thanks again to G. M. Grena for alerting us.

Now, to an article by Bloomberg about Qeiyafa which includes two quotations from scholars. The first is from N. A. Silberman, known for his extreme views that much of the Old Testament was written very late by priestly propagandists.

“To find an apple tree in some town in the Midwest doesn’t mean the Johnny Appleseed legend is exactly correct,” said Silberman, co-writer with Israel Finkelstein of “The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts.”

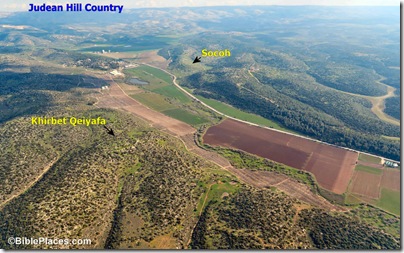

This is really quite an apt analogy. Except for the fact that the site was found precisely in the exact area where the battle of David and Goliath was fought. And it dates precisely to the time period when the Bible says that David lived. Sorry, sir, you can’t wish this away so easily.

The excavator of Qeiyafa, unfortunately, doesn’t do much better.

Garfinkel, gesturing toward a nearby hill where he said the Philistine city of Gath once stood, said he believes his find brings to life the tale of David killing the Philistine giant Goliath with just two stones.

He said he would have agreed with Silberman’s views on David before the dig: “Once it was excavated, it changed the whole situation.”

So until this summer Garfinkel apparently held to the view that Silberman espouses, which is that Judah was a sparsely populated hinterland during the time of David (and for the next several hundred years). But he finds a small walled city and a potsherd with writing on it, and suddenly, everything has changed? This tells me either that he has a super-high estimation of the value of what he found, or he is ignorant of some important data. How does Qeiyafa revolutionize things when decades ago, a much more impressive fortification from the 10th century was found at Gezer (11 miles to the north)? What about Azekah about 1 mile to the west? True, it hasn’t been excavated (by someone other than Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister 100 years ago), but shouldn’t that very fact give someone (both Silberman and Garfinkel) pause before concluding that Judah was weak and impoverished in the “time of David”? Who knows what you’ll find at Azekah! Just down the road is Gath, which is proving to look quite similar to what we would expect from the biblical account.

Now, perhaps Garfinkel was speaking not of the (lack of unique) fortifications, but rather of the ostracon. Surely, this is an important discovery. Just how important we may not know until the text is recovered by photography and it is published. But, is it really accurate to say that on the basis of this one as-yet-undeciphered ostracon that “it changes the whole situation”? It’s not like we don’t have other 10th century inscriptions from the area–the Gezer Calendar has been known for 100 years, and the Tel Zayit inscription was discovered a few years ago. So we have known that ancient Judah was literate and had fortified cities in the Shephelah for a long time now. But Garfinkel (apparently) denied these realities meant anything because he would have agreed with Silberman’s views. But now, on the basis of his finds, everything has changed in his mind. This all suggests to me that some scholars come to conclusions without carefully considering all of the evidence.

Chris Heard at Higgaion has posted a few comments that I want to note. The first point is outstanding and in sharp contrast to the two quotes above:

Reports of the “low chronology’s” death may be greatly exaggerated, or premature, but Khirbet Qeiyafa must surely influence our picture of 10th-century Judah. Let us not overstate the case: what we (the interested public) know of Khirbet Qeiyafa at this point hardly “proves that David killed Goliath” or anything of that sort. However, Khirbet Qeiyafa does counterbalance the increasingly common portrayal of 10th-century Judah as a cultural backwater.

Yes, indeed. Overstatements are far too common among scholars talking to journalists. But this part I cannot agree with:

The identification of the site as Sha‘arayim seems quite likely now, completely independent of anything learned from the ostracon.

This conclusion is unwarranted on the basis of the current evidence. It seems to rely on the excavator’s word, and not the data. But I urge caution. 1) Last year the excavator said the site was Azekah. Frankly, that’s most unlikely on many accounts. It comes from the urge to have your site be something important. It demonstrates that the excavator did not properly consider the data from history and geography in making the identification. 2) Historical geography seems to have been ignored in this identification of Qeiyafa as Shaaraim as well. I have discussed this before and will be saying more about it. 3) The sole basis for identifying Qeiyafa as Shaaraim is this: Shaaraim means “two gates.” (The three reasons listed on slide 33 all argue against identifying Qeiyafa as Shaaraim, which I will demonstrate in the future.) The excavator has excavated one and eyeballed what he believes is another one from the same time period. No excavations have been done of the second gate. The meaning of the name is significant, but my question is: does it override other evidence?

Again, I simply suggest that more study occur before we decide that the identification as Shaaraim “seems quite likely now.”

If all of this is too basic for you and you’d prefer to read about some analysis about radiocarbon dating related to Qeiyafa, see this post by Abnormal Interests. John Hobbins also has some more thoughts about the site identification, to which I’ll respond in the future aforementioned post.

Update (12/5): I have removed reference to the Ephes-dammim credit line in the pdf file as that has

now been updated (see comment below).