(Post by Seth M. Rodriquez)

In 1 Corinthians 11:17-34, Paul describes an extremely dysfunctional church event. When the church gathered to observe the Lord’s Supper, there were divisions and factions (v. 18-19) due to the fact that people were not sharing food with those who were hungry and were eating before the others arrived (vv. 21, 33-34). What could have possessed them to act in such an unloving way during one of the holiest events in the life of their church?

In his book St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology, Jerome Murphy-O’Connor suggests a historical context which could help explain this passage. His suggestion centers around the fact that wealthy homes in that culture typically had two public areas: a room just inside the entrance called an atrium and a dining room called a triclinium.

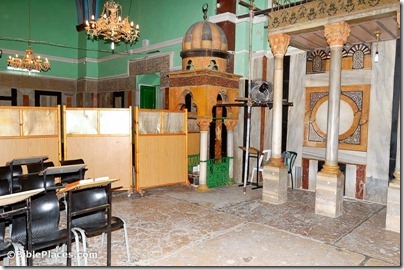

Our picture of the week is an example of an atrium found in one of the houses at Pompeii. This photo comes from Volume 14 of the revised and expanded version of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands, which focuses on Italy and Malta. The photo is entitled, “Pompeii House of Sallust Atrium.” An atrium typically had a a rectangular pool in the center of the room called an impluvium.

Murphy-O’Connor suggests that part of the problem in the Corinthian church was due to the fact that a small group of the wealthiest church members were invited to dine in the triclinium while the rest of the members had to sit in the atrium. He explains a hypothetical historical background in the following way:

Private houses were the first centers of church life. Christianity in the 1st cent. A.D., and for long afterwards, did not have the status of a recognized religion, so there was no question of a public meeting-place, such as the Jewish synagogue. Hence, use had to be made of the only facilities available, namely, the dwellings of families that had become Christian. …

Given the social conditions of the time, it can be assumed that any gathering which involved more than very intimate friends of the family would be limited to the public part of the house …

… [T]he average size of the atrium is 55 sq. meters and that of the triclinium 36 sq. meters. Not all this area, however, was usable. The effective space in the triclinium was limited by the couches around the walls; the rooms surveyed would not have accommodated more than nine, and this is the usual number …. The impluvium in the center of the atrium would not only have diminished the space by one-ninth, but would also have restricted movement; circulation was possible only around the outside of the square. Thus, the maximum number that the atrium could hold was 50, but this assumes that there were no decorative urns, etc. to take up space, and that everyone stayed in the one place; the true figure would probably be between 30 and 40. …

The mere fact that all could not be accommodated in the triclinium meant that there had to be an overflow into the atrium. It became imperative for the host to divide his guests into two categories; the first-class believers were invited into the triclinium while the rest stayed outside. Even a slight knowledge of human nature indicates the criterion used. The host must have been a wealthy member of the community and so he invited into the triclinium his closest friends among the believers, who would have been of the same social class. The rest could take their places in the atrium, where conditions were greatly inferior. Those in the triclinium would have reclined, as with the custom … where as those in the atrium were forced to sit ….

The space available made such discrimination unavoidable, but this would not diminish the resentment of those provided with second-class facilities. Here we see one possible source of the tensions that appear in Paul’s account of the eucharistic liturgy at Corinth (1 Cor 11:17-34). However, his statement that “one is hungry while another is drunk” (v. 21) suggests that such tensions were probably exacerbated by another factor, namely, the type of food offered. …

The reconstruction is hypothetical, but no scenario has been suggested which so well explains the details of 1 Cor. 11:17-34. The admonition “wait for one another” (v. 34) means that prolambano in v. 21 necessarily has a temporal connotation; some began to eat before others. Since these possessed houses with plenty to eat and drink (vv. 22, 34), they came from the wealthy section of the community and might have made a contribution in kind to the community meal. This, they felt, gave them the right to think of it as ‘theirs’ (to idion deiphon). Reinforced by the Roman custom they would then have considered it their due to appropriate the best portions for themselves. Such selfishness would necessarily include a tendency to take just a little more, so that it might happen that nothing was left for the ‘have-nots’ (v. 22), who in their hunger had to content themselves with the bread and wine provided for the Eucharist. However, as Paul is at pains to point out, under such conditions no Eucharist is possible (v. 20).

Excerpt is taken from Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology, Good News Studies, vol. 6 (Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, Inc, 1983), 153-161, and can be purchased here. This and other photos of Pompeii are included in Volume 14 of the Pictorial Library of Bible Lands and can be purchased here. More information on Pompeii and additional photos (including another atrium) can be found on the BiblePlaces website here.