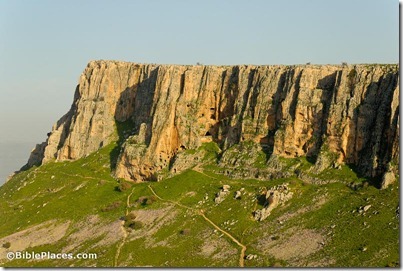

Recent discoveries of a cultic significance were announced today in a press conference at Hebrew University. Archaeologists Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor believe that they have found religious objects from the time of King David at Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Shephelah of Judah.

The three shrines are part of larger building complexes. In this respect they are different from Canaanite or Philistine cults, which were practiced in temples – separate buildings dedicated only to rituals. The biblical tradition described this phenomenon in the time of King David: “He brought the ark of God from a private house in Kyriat Yearim and put it in Jerusalem in a private house” (2 Samuel 6).

The cult objects include five standing stones (Massebot), two basalt altars, two pottery libation vessels and two portable shrines. No human or animal figurines were found, suggesting the people of Khirbet Qeiyafa observed the biblical ban on graven images.

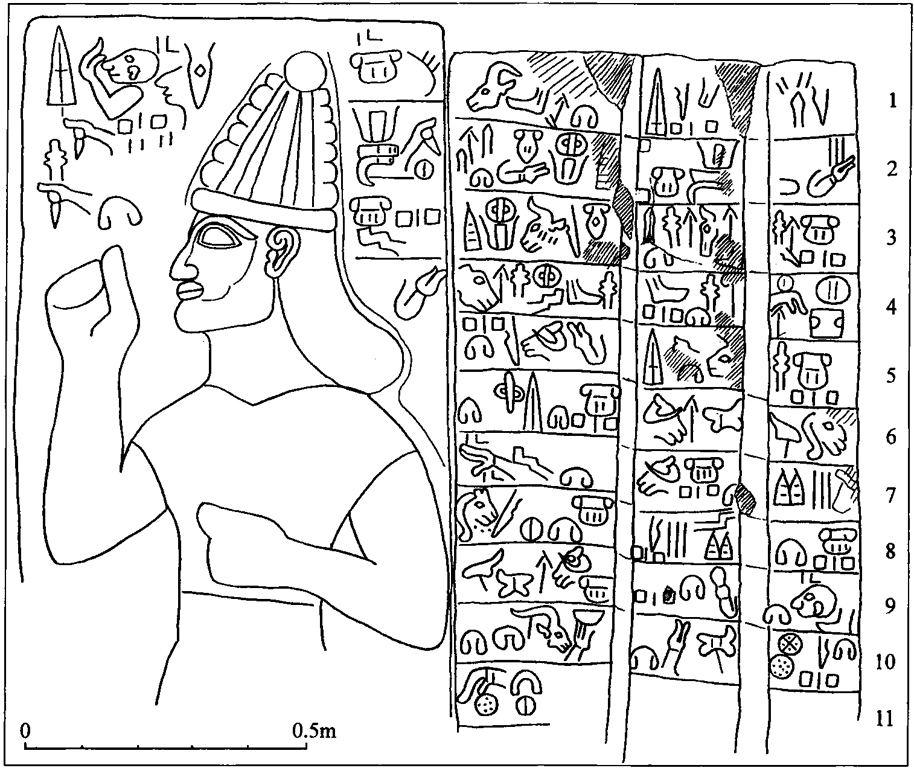

The two portable shrines are of great interest and may help us to understand some difficult terms in the Hebrew Bible.

Two portable shrines (or “shrine models”) were found, one made of pottery (ca. 20 cm high) and the other of stone (35 cm high). These are boxes in the shape of temples, and could be closed by doors.

The clay shrine is decorated with an elaborate façade, including two guardian lions, two pillars, a main door, beams of the roof, folded textile and three birds standing on the roof. Two of these elements are described in Solomon’s Temple: the two pillars (Yachin and Boaz) and the textile (Parochet).

The stone shrine is made of soft limestone and painted red. Its façade is decorated by two elements. The first are seven groups of roof-beams, three planks in each. This architectural element, the “triglyph,” is known in Greek classical temples, like the Parthenon in Athens. Its appearance at Khirbet Qeiyafa is the earliest known example carved in stone, a landmark in world architecture.

The second decorative element is the recessed door. This type of doors or windows is known in the architecture of temples, palaces and royal graves in the ancient Near East. This was a typical symbol of divinity and royalty at the time.

The press release has more details. The archaeologists believe that the site is Israelite because of the absence of pig bones and graven images.

Do these discoveries undermine the biblical narrative of Israelite monotheism? Such is the insinuation of the archaeologists.

The biblical tradition presents the people of Israel as conducting a cult different from all other nations of the ancient Near East by being monotheistic and an-iconic (banning human or animal figures). However, it is not clear when these practices were formulated, if indeed during the time of the monarchy (10-6th centuries BC), or only later, in the Persian or Hellenistic eras.

In other words, the presence of cultic material outside of Jerusalem challenges the biblical claim that Israelites worshipped only one God in one place. But there is no such biblical claim. Scripture is very clear that though the Lord commanded the Israelites to worship only at the central altar (Deut 12), the Israelites perennially failed to keep this command. The Bible is very open about this failure, recording stories such as Gideon’s idolatry (Judg 8:27); Micah’s shrine (Judg 17-18), and Saul’s pursuit of witchcraft (1 Sam 28). David was very mindful of the temptations:

Psalm 16:4 (NIV) — The sorrows of those will increase who run after other gods. I will not pour out their libations of blood or take up their names on my lips.

What discoveries like these from Qeiyafa show is not that monotheism evolved only late in Israel’s history but that God’s covenant people failed to worship in the prescribed way, just as the Bible records.