I recently saw an announcement for a brand new volume by David Chapman and Eckhard Schnabel that collects together all extra-biblical texts relevant to understanding the trail and crucifixion of Jesus. The book is entitled The Trial and Crucifixion of Jesus: Texts and Commentary. It caught my eye because I find Schnabel’s writing to be very thorough and helpful. Several books on crucifixion, in fact, have appeared in the last few years from the same publisher.

Chapman, David W.

2008 Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 244. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Republished by Baker Academic, 2010.]

The bulk of this volume is devoted to an inductive study of the ancient sources regarding crucifixion with an eye to understanding the way in which Jews perceived crucifixion. Here Chapman discusses ancient texts from various types of literature that can be described as Jewish (e.g., the Apocrypha, Josephus, Philo, rabbinics, etc.). Chapman’s survey reveals a variety of perceptions from martyrdoms to scandalous punishments for brigands and rebels…Concerning the primary sources, it seems that Chapman has not missed any significant extant material….Although acknowledging the existence of various methods and devices, [Chapman] is not claiming that Jesus died on a pole (or other device); rather, he says crucifixion could take place in a number of ways…The goals of crucifixion included torture, shame, and death. How the cross looked or what shape it was in was not the main concern. (Review by Joseph D. Fantin.)

Samuelsson, Gunnar.

2013 Crucifixion in Antiquity: An Inquiry into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion. 2nd ed. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 310. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

This work is a semantic study of the Greek words typically translated “crucify” or “crucifixion.” Prior to its release, popular media tried to create controversy out of the book’s “sensational” claim that the Greek terms do not refer specifically to crucifixion, but only generally to suspension.

Gunnar Samuelsson investigates the philological aspects of how ancient Greek, Latin and Hebrew/Aramaic texts depict crucifixions. A survey of the texts shows that there has been too narrow a view of the “crucifixion” terminology. The various terms do not only refer to “crucify” and “cross.” They are used much more diversely. Hence, most of the crucifixion accounts that scholars cite in the ancient literature have to be rejected, leaving only a few. (From the publisher’s website.)

Cook, John Granger.

2014 Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 327. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

This work, originally conceived as a revision of Hengel’s work on the subject, is in some ways a response to Samuelsson. It casts a wider net by investigating Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic texts, as well as pictorial representations and archaeological evidence. A very brief summary can be found at the Bible and Interpretation website.

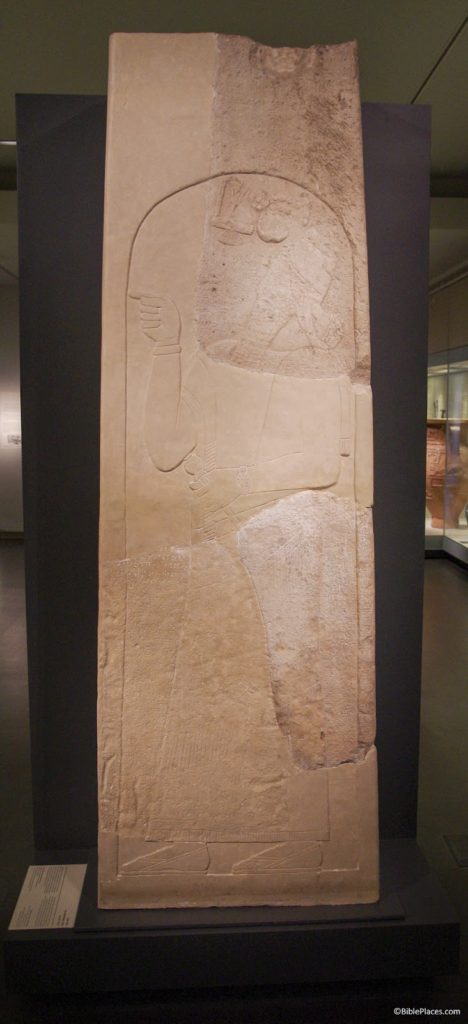

To understand the phenomenon of Roman crucifixion, the author argues that one should begin with an investigation of the evidence from Latin texts and inscriptions (such as the lex Puteolana [the law of Puteoli]) supplemented by what may be learned from the surviving archaeological material (e.g., the Arieti fresco of a man on a patibulum [horizontal beam], the Puteoli and Palatine graffiti of crucifixion, the crucifixion nail in the calcaneum bone from Jerusalem, and the Pereire gem of the crucified Jesus [III CE]). This evidence clarifies the precise meaning of terms such as patibulum and crux (vertical beam or cross), which in turn illuminate the Greek terms [e.g., σταυρός, σταυρόω and ἀνασταυρόω] and texts that describe crucifixion or penal suspension. It is of fundamental importance that Greek texts be read against the background of Latin texts and Roman historical practice. The author traces the use of the penalty by the Romans until its probable abolition by Constantine and its eventual transformation into the Byzantine punishment by the furca (the fork), a form of penal suspension that resulted in immediate death (a penalty illustrated by the sixth century Vienna Greek codex of Genesis). Cook does not neglect the legal sources — including the question of the permissibility of the crucifixion of Roman citizens and the crimes for which one could be crucified. In addition to the Latin and Greek authors, texts in Hebrew and Aramaic that refer to penal suspension and crucifixion are examined. Brief attention is given to crucifixion in the Islamic world and to some modern forms of penal suspension including haritsuke (with two photographs), a penalty closely resembling crucifixion that was used in Tokugawan Japan. The material contributes to the understanding of the crucifixion of Jesus and has implications for the theologies of the cross in the New Testament. The relevant ancient images are included. (Abstract from author’s Academia.edu page.)

Chapman, David W., and Eckhard J. Schnabel.

2015 The Trial and Crucifixion of Jesus: Texts and Commentary.

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 344.

Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

The purpose of this comprehensive sourcebook by David W. Chapman and Eckhard J. Schnabel is to publish the extra-biblical primary texts that have been cited as relevant for understanding Jesus’ trial and crucifixion. The texts in the first part deal with Jesus’ trial and interrogation before the Sanhedrin, and the texts in the second part concern Jesus’ trial before Pilate. The texts in part three represent crucifixion as a method of execution in antiquity. For each document the authors provide the original text (Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Latin, etc.), a translation, and commentary. The commentary describes the literary context and the purpose of each document in context before details are clarified, along with observations on the contribution of these texts to understanding Jesus’ trial and crucifixion. (From the publisher’s website.)

Table of Contents

Part 1. The Jewish Trial before the Sanhedrin (E. J. Schnabel)

1.1 Annas and Caiaphas

1.2 The Jurisdiction of the Sanhedrin

1.3 Capital Cases in Jewish Law

1.4 Interrogation of Witnesses

1.5 The Charge of Blasphemy

1.6 The Charge of Being a Seducer

1.7 The Charge of Sorcery

1.8 Abuse of Prisoners

1.9 Transfer of Court Cases

Part 2. The Roman Trial before Pontius Pilatus (E. J. Schnabel)

2.1 Pontius Pilatus

2.2 The Jurisdiction of Roman Prefects

2.3 The crimen maiestatis in Roman Law

2.4 Reports of Trial Proceedings

2.5 Languages Used in Provincial Court Proceedings

2.6 Amnesty and Acclamatio Populi

2.7 Abuse of Convicted Criminals

2.8 Requisitioning of Provincials

2.9 Carrying the Crossbeam

2.10 Titulus

Part 3. Crucifixion (D. W. Chapman)

3.1 Crucifixion, Bodily Suspension, and Issues of Definition

3.2 Bodily Suspension in the Ancient Near East

3.3 Barbarians and Crucifixion according to Graeco-Roman Sources

3.4 Suspension and Crucifixion in Classical and Hellenistic Greece

3.5 Jewish Suspension and Crucifixion

3.6 Victims of Crucifixion in the Roman Period

3.7 Suspension and Crucifixion in Hellenistic and Roman Palestine

3.8 Methods and Practices of Bodily Suspension in the Roman Period

3.9 Crucifixion Terminology Applied to Earlier Traditions

3.10 Perceptions of Crucifixion in Antiquity

3.11 Reception of the Christian Message of the Crucified Messiah