For an introduction to this series see here.

The Benshoof Cistern Museum houses the remains of three Late Bronze-early Iron Age I (1550-1100) tombs discovered at Tel Dothan (Genesis 37:17, 2 Kings 6:13) during the Joseph Free-lead excavations in the 1950-1960s. The small exhibit is inside of a Roman/Byzantine cistern on the campus of St. George Cathedral and College in East Jerusalem.

Directions

View Secret Places: BiblePlaces in a larger map

This small museum is situated next to several important historical, archaeological and research sites such as, The Tombs of the Kings, the Garden Tomb, exposed sections of Josephus’ Third Wall, the American Colony, the Albright Institute, and the Ecole Biblique (French Archaeological School). It is also very close to several of Jerusalem’s largest hotels (e.g. Olive Tree, Dan Panorama, etc.) near highway 60.

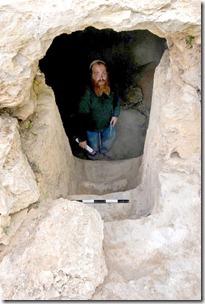

To get to the museum it is advised that you use the above Google Map to find St. George Cathedral as backroads (and sometimes main roads) in Jerusalem are notoriously tricky for new visitors and even long-term residents. Upon entering St. George, either from the main entrance on Nablus/Shechem Street or the back entrance on Salahdin Street, you should walk through the campus to the center of the compound where you will find a door with a nice welcome sign (see picture below), which will lead you down into the exhibit.

|

| Entrance to Benshoof Cistern Museum |

Entrance Information

Admission is free. The hours of operation are from 8:00 am-2:00 pm Tuesday-Saturday and by appointment for other times (972-2-626-4704). The lady who curates the museum is quite pleasant and very excited to show off the remains for those interested – even if your visit is slightly after hours or unannounced (personal experience on both counts).

Touring Suggestion

Depending on your level of interest and the size of your group you should estimate between 20-30 minutes to view the cistern exhibit.

Museum Information and Some Personal Thoughts

The materials in the museum were excavated by Joseph Free in the 1950s, but were not published until the mid-1990s by Robert Cooley who was in charge of publishing the rest of the material from the site (see here for the most recent final publication of Dothan from the excavations carried out on the tell). The majority of the objects come from Tomb 1 – which according to the museum pamphlet is “one of the largest single-chambered cave burials of the Late Bronze and early Iron Ages to have been excavated in the Levant.” It is estimated that 250-300 Canaanites were buried inside of this cave, over 3,000 pottery vessels, ca. 100 personal ornaments, ca. 100 weapons were found with the skeletal remains (per pamphlet).

One of the great strengths of this exhibit is the well-defined organization of the various types of pottery. Someone interested in such things as ceramic typology of the Bronze-Iron Age might be intrigued by seeing whole shelves filled with LB-Iron I lamps, chalices/goblets (see picture below), kraters, bowls, pyxides, lamps, and more (links to wikipedia description are meant to describe the form of the vessel not the specific type that you would see at this museum).

|

| Low-quality picture of High-quality Canaanite Late Bronze Age Chalices and Goblets found in the Western Cemetery of Tell Dothan

I was especially intrigued by their large collection of chalices, as these seem identical to the types of chalices and goblets that our team has been uncovering inside of a very interesting, seemingly cultic related Late Bronze age building at Tel Burna. Shameless plug alert! Come join us in a week-and-a-half for our spring season – April 21-25, or June 2-21 for our summer season and find these for yourself. 🙂

Due to the high quantities of consuming and serving vessels, particularly the large amount of kraters of a wide-variety of forms (used for wine-mixing), and the existence of animal bones the excavators concluded that these tombs were used for feasting in commemoration of dead ancestors.

This funerary feast is commonly referred to as the marzeah, based upon some biblical references (Amos 6:7, Jeremiah 16:5; 8) and extra-biblical parallels (e.g. Ugarit). In relation to this, the museum pamphlet (this seems to have been written by Robert Cooley) says the following:

Conclusion

Where does this museum fit into the wider spectrum of available archaeological exhibits in Israel?

It certainly should be considered “specialist” in the sense that it is quite small and deals with a single period related to a single people – the Canaanites. However, it is also “special” in that it allows visitors to visit a significant element of a site that is largely inaccessible (Dothan) and to better understand the enigmatic ancient Near Eastern practice of ancestor funerary feasting. Which if nothing else gives a great ancient background for the modern urban practice of “pouring one out for your homies.” 🙂 |