If I were teaching a course in historical geography now to advanced students, I’d cancel one of the assignments and have them write a paper on the site identification of Khirbet Qeiyafa. They would be required to use all of the available data in suggesting possible candidates. Since I’m not teaching such a class, I can post my own thoughts here without fear of hindering their research.

It’s been a few weeks since I wrote about Kh. Qeiyafa, so a brief review is in order: Located next to the Elah Valley where David fought Goliath, Kh. Qeiyafa has been excavated the last two seasons (2007-08). This summer a 10th century B.C. inscription (ostracon) was discovered (photo), the contents of which have not yet been revealed, but may be very interesting.

The place to start in identifying Kh. Qeiyafa with a known historical place name is to look at the general area of the site. Kh. Qeiyafa is located on the north side of the Elah Valley, roughly north of probable Socoh (Kh. Abbad/Kh. es-Suweikeh) and east of probable Azekah (Tell Zakariyeh). Those last two identifications are generally agreed upon by scholars, but as far as I know there’s no certain proof of either identification (for a good discussion of Socoh and Azekah, see The Sacred Bridge, page 147). That’s important to keep in mind as we proceed under the assumption that Abbad = Socoh and Zakariyeh = Azekah.

Early explorers who identified sites like Hazor, Beth Shemesh, and Beth Shean did not have the advantage of aerial photographs and Google Earth. But since we have those at our disposal, we will put them to use.

You can locate Qeiyafa on Google Earth using this kmz file.

You can locate Qeiyafa on Google Maps with this link (via G. M. Grena)

You can see the site in relation to Socoh (Abbad) and the Elah Valley on the photo below.

Archaeology is critical in determining site identification, and Qeiyafa has remains dating to the early 10th century and to the Hellenistic period. To do a thorough job in my little exercise, one would need to investigate Hellenistic sources concerning sites given in this area. Because the occupation gap is so large (c. 800 years), it is possible that the Iron Age name was not preserved. Since I am less knowledgeable about Hellenistic sources, and don’t have the necessary time, I am going to ignore this part of the equation.

The textual sources that we have for this time period are limited. The Bible is the obvious place to start, though as I’ll note, some scholars question the traditional dates given to biblical texts. Another source is the ostracon previously discussed. It is possible that this ostracon has one or more place names and may single-handedly answer this question. (Well, not really single-handedly, as it has to be in agreement with the rest of the data, but its relative importance is potentially great.) Another possible source is Shishak’s conquest list as given on the Bubastite Portal in the Karnak Temple.

Since no other sites in the vicinity of the Elah Valley appear to be mentioned by Shishak, I am going to ignore that for now.

What can we learn from the Bible? It might be instructive to note first that many scholars these days would sneer at this question. It then would be worth reviewing just how many hundreds of accurate site identifications were made in the last 150 years, using the Bible as the primary source. That is how Edward Robinson did it, as well as many successors on down to Yohanan Aharoni and his students and “grandstudents” (among whom I count myself).

A good place to start is with the passage of the battle of David and Goliath, as this was situated in the Elah Valley. The setting is given in 1 Samuel 17:1:

Now the Philistines gathered their armies for battle. And they were gathered at Socoh, which belongs to Judah, and encamped between Socoh and Azekah, in Ephes-dammim (ESV).

Aerial view of Elah Valley, view to southeast

While the locations of Socoh and Azekah are generally agreed upon (see above), the location of Ephes-dammim is uncertain. Based on the above text, it seems that it is located “between” the two sites. “Pas Dammim” is mentioned in 1 Chronicles 11:13 and could well be the same place, though the event described there is a different one than the David and Goliath story. A parallel to 1 Chron 11:13 is given in 2 Samuel 23:9; the place name is lacking in the Masoretic Text but is given as “Pas Dammim” in the Septuagint. These are the only references to Ephes/Pas Dammim in the Bible.

In teaching the David and Goliath story, I’ve pointed to the “gas station” (labeled on the first photo above) as a possible place for Ephes-dammim. There’s no evidence for this, but since no other site has been identified and this sits neatly between Azekah and Socoh on the southern ridge of the valley, it was a convenient marker.

But now a new possibility arises: Could Khirbet Qeiyafa be Ephes-dammim? There are three points in favor of this identification:

1) Like Ephes-dammim (ED), Qeiyafa is “between” Azekah and Socoh;

2) Like ED, Qeiyafa was inhabited in the 10th century;

3) Since the only textual references to ED are in the 10th century, and Qeiyafa was inhabited only in the 10th century (during the time of the Bible), this too would match. [Note: the biblical chronology seems to put the David/Goliath battle in the late 11th century, but the difference is only a few decades here and archaeology is usually not able to be very precise, especially at this period of time.]

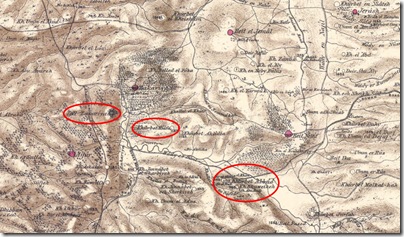

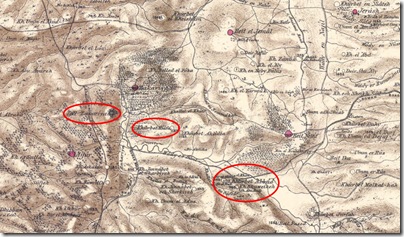

Kiafa (Qeiyafa) is clearly between Azekah and Socoh; map from Survey of Western Palestine (1870s)

Kiafa (Qeiyafa) is clearly between Azekah and Socoh; map from Survey of Western Palestine (1870s)

Some have suggested that the modern site of Damun preserves the name of Ephes-dammim, but as Steven Ortiz notes in the Eerdman’s Dictionary of the Bible (p. 411), Damum is 4 miles (6.5 km) northeast of Socoh when one would expect it to be west (and east of Azekah).

Another possible text that lists cities from the 10th century (though many scholars think it dates to much later) is the list of Rehoboam’s fortifications (2 Chronicles 11:5-10): “Rehoboam lived in Jerusalem and built up towns for defense in Judah: Bethlehem, Etam, Tekoa, Beth Zur, Soco, Adullam, Gath, Mareshah, Ziph, Adoraim, Lachish, Azekah, Zorah, Aijalon and Hebron.” The location of nearly all of these sites is pretty well agreed on, not suggesting another possibility for Qeiyafa.

A text that many scholars would go to for sites is the city list of Judah from Joshua 15. Clearly this is the best geographical list for the area, but I didn’t start there because I believe (hold your breath) that this list dates hundreds of years earlier than the 10th century. Most scholars do not, and accordingly, I will not ignore it. Joshua 15:33-36 lists cities of Judah: “In the western foothills: Eshtaol, Zorah, Ashnah, Zanoah, En Gannim, Tappuah, Enam, Jarmuth, Adullam, Socoh, Azekah, Shaaraim, Adithaim and Gederah (or Gederothaim)—fourteen towns and their villages.” The location of many of these cities is not positively identified. Based on the sites whose identification is generally agreed on (Eshtaol, Zorah, Jarmuth, Adullam, Socoh, Azekah), the list seems to proceed from north to south. The Elah Valley sites are all known (Adullam, Socoh, Azekah), and do not give us an extra name to associate with Qeiyafa, particularly between Socoh and Azekah as we might expect from 1 Sam 17:1. If Joshua 15 is a pre-10th century text, then this is not surprising.

The “prophet of the Shephelah” is Micah, who lived in the late 8th century. His hometown is given as Moresheth (probably known elsewhere as Moresheth-gath) in Micah 1:1. He pronounces judgment on many cities in the Shephelah from 1:10-16, a number of which are unknown (particularly in vv. 11-12). Too little is stated to pin down locations for these (Beth Ophrah, Shaphir, Zaanan, Beth Ezel, Maroth), but none is mentioned in connection with Adullam, a city on the eastern end of the Elah valley. Again, I wouldn’t expect to find a relevant name here since Qeiyafa was apparently abandoned several hundred years earlier.

View from Socoh looking west towards Azekah

View from Socoh looking west towards Azekah

Are there other possibilities? A quick check of Ahituv’s Canaanite Toponyms in Ancient Egyptian Documents, Tabula Imperii Romani, and Eusebius’s Onomasticon do not seem to suggest any other potential site names.

Was Kh. Qeiyafa a Philistine outpost? This summer the excavations discovered a four-chambered

city gate and a 13-foot-wide (4 m) casemate wall. (Photos of excavations here and a 4-minute video of mostly still photos here.) It certainly was a stronghold, and the only two known powers of the region at this time were the Philistines and the Israelites. The Egyptians were back home enjoying their Third Intermediate Period, and there does not seem to be any strong contingent of Canaanites in the Shephelah (those would have likely migrated to where there were fewer enemies, such as the Jezreel Valley).

We can speculate further. Perhaps Kh. Qeiyafa was Ephes-dammim, and it was constructed by the Israelites in the 11th century as they competed with Philistia for the Shephelah. But one day the Philistines succeeded in capturing the fortress. That brought Saul and the Israelites down to battle to regain their stronghold. That could explain the otherwise curious reference in 1 Sam 17:1 to Ephes-dammim, as well as to giving its specific coordinates (since it was not well-known, then or later).

Unfortunately for the Israelites, Goliath wanted to make the battle a contest of champions and there was no one brave enough among the Israelites to respond. The Israelites were encamped opposite the Philistines on the south side of the valley (which is the opposite of how I have always pictured it), or possibly in the hill country to the east. David’s victory sent the Philistines fleeing towards Gath and Ekron (1 Sam 17:52), which makes perfect sense given the location of Kh. Qeiyafa.

While the above paragraph is speculative, the data that connects Qeiyafa with Ephes-dammim seems to me to be stronger than that which exists for many biblical sites. The biblical text is very specific, and Qeiyafa matches exactly. The dating of the fortress to the early 10th century is very close as well. It’s certainly intriguing to consider. Perhaps the ostracon discovered this summer will help to relate Kh. Qeiyafa to the biblical narrative, or even to confirm/deny the possibility that the site is biblical Ephes-dammim. We’ll be interested to learn more when details are released.