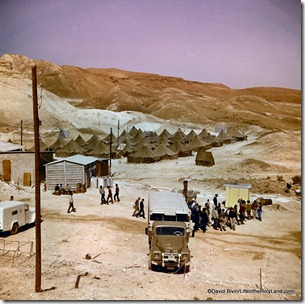

David Hendin describes the conclusion of a two-week season of excavating at Sepphoris with Eric and Carol Meyers.

Israel’s water crisis is over, says the former head of the Water Authority. No, it’s not, says the Authority’s spokesman. “We will be under the red line this summer in all three main reserves.”

Giovanni Pettinato, well known for his work in translating the Ebla tablets, has passed away.

John Lund, a 70-year-old tour guide from Utah, was arrested this week in Israel for selling stolen antiquities. He allegedly made $20,000 from recent sales, but only had to post bail of $7,500. (Does that make sense to anyone else?) James Davila faults the media for calling Dr. Lund an Egyptologist despite the fact that “he is a retired adjunct lecturer in areas that have nothing to do with ancient history.” He concludes that, “it has become obvious that the media could not identify an Egyptologist if one rose up from an alabaster coffin in front of them”!

A number of interesting travel pieces have been written in the last week or two:

Ferrell Jenkins has located a portion of the Roman road in the eastern Galilee near the Golani Junction.

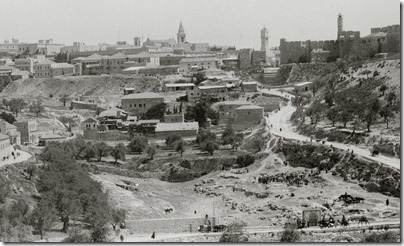

Jenkins also points out Carl Rasmussen’s photos that reveal just how oppressive a khamsin in Jerusalem is.

Shmuel Browns describes Mount Arbel and what you can see on a hike in the area.

Joe Yudin takes his readers to the places of Gideon’s life, including his hometown of Ophrah, the Hill of Moreh, and the Spring of Harod.

Wayne Stiles continues his weekly “Sights and Insights” column with a visit to Tel Arad’s Early Bronze and Iron Age cities.

Jonathan Goldstein investigates some of the more modern attractions in Nazareth.