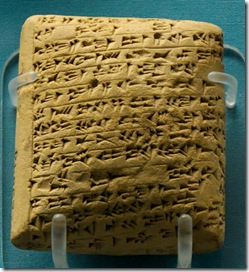

Christopher Rollston has written a brief analysis of the recent IEJ report on the Jerusalem cuneiform tablet fragment.

Strikingly, the authors conclude that “given the fact that the tablet is written on clay from the Jerusalem region and that its find site is close to what must have been the acropolis of Late Bronze Age Jerusalem, there is good reason to believe that the letter fragment does, in fact, come from a letter of a king of Jerusalem, mostly likely an archive copy of a letter from Jerusalem to Pharaoh” (emphasis mine). It is also contemplated that, for Jerusalem 1, the “Jerusalem King in question could be Abdi-Heba,” but the authors also state “but again perhaps not, since Jerusalem 1 does not include any specific feature that would tie it directly to El Amarna 285-290.” They then conclude that “in short, the ductus of our letter fragment would be appropriate for a finely written letter from a king of Jerusalem to the Egyptian court.” It is with the probability of these historical conclusions and Sitz im Leben that I wish respectfully to differ.

He then makes eight observations before concluding that the text “could be one of various things . . . e.g., an epistolary text, a legal text, an administrative text, a literary text.”

You can read the whole piece here.

HT: Paleojudaica