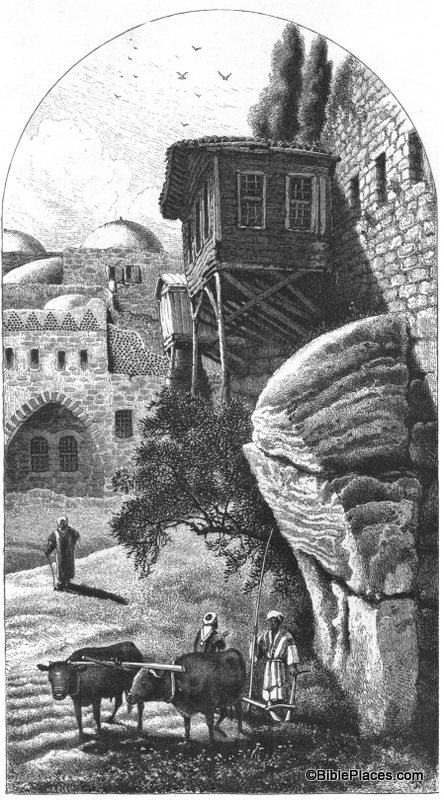

Robinson’s “Arch” is really just the lowest section of what was originally an arch. It is called Robinson’s Arch because it was discovered by Edward Robinson in the 1830s. You can see the remains of the arch on the right half of this drawing, towering above the two men and the oxen. The arch originally spanned across the Tyropean Valley in Jerusalem and formed the upper section of a long stairway that provided access to the Temple Mount during the time of Christ. (A reconstruction of this stairway can be seen here.) The Tyropean Valley was filled in over the years, beginning with the destruction of the Temple by the Romans in A.D. 70. Over the centuries the area was built up and torn down over and over again, accumulating debris until it looked like this in the nineteenth century.

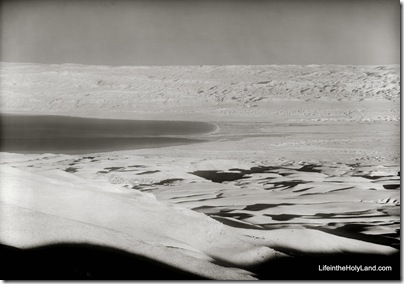

Returning to our question (“How much dirt does an archaeologist have to move?”), archaeologists in the 1960s–1990s had to move several meters of debris during their excavation of this area. The picture above is what the area looked like in the 1870s. Compare that with what it looks like today:

This picture (taken from the Jerusalem volume of the PLBL) is looking at Robinson’s Arch from the opposite direction as the drawing in Picturesque Palestine. The arch is at the top of the photograph and circled in red in this photo. You can see that it now towers over the remains of the 1st-century street below. If you look carefully, there is a person standing on the street looking up at the arch. That gives you an idea of the massive amount of dirt and stone that had to be moved by the excavation teams in recent decades.

This is just one example of the value of a work such as Picturesque Palestine. It allows us to roll back the clock and see how the land appeared to the nineteenth century explorers before the excavations of the last 100 years.

This and other pictures of nineteenth-century Jerusalem are available in Picturesque Palestine, Volume I: Jerusalem, Judah, and Ephraim and can be purchased here. Additional historic images of the Temple Mount can be seen here and here on the LifeInTheHolyLand.com website. Several websites related to this topic can be found on the BiblePlaces website here.