(Post by A.D. Riddle)

Oftentimes, while researching archaeological sites and/or biblical places, I come across things like this:

map reference 193.142

M.R. 219156

1972 1954

These are grid coordinates for sites. One encounters them in key works such as The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Sites in the Holy Land (5 vols.), Anchor Bible Dictionary, or the volumes from the archaeological survey of Israel. I want to locate these sites in Google Earth, but how do I convert them? (This subject came to mind while reading Chris McKinny’s post on Shaaraim [see here].)

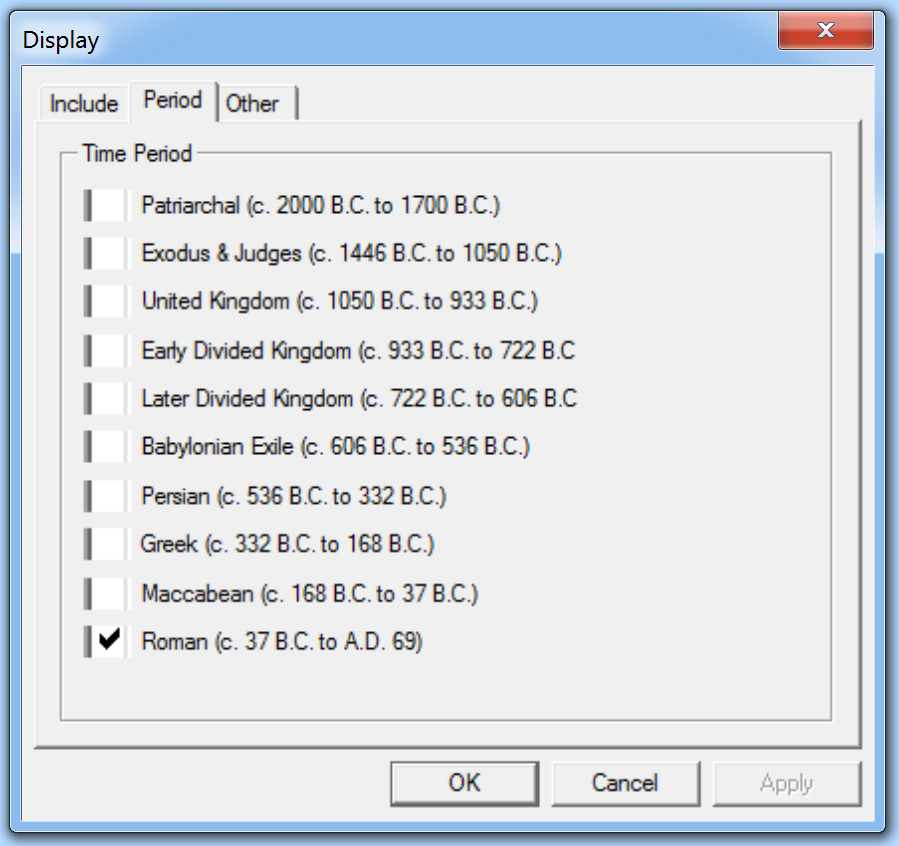

There are two coordinate systems for Israel, the Old Israeli Grid and the New Israeli Grid. Sometimes these are abbreviated OIG or NIG, but typically no indication is given as to which coordinate system is being used. (To read more about OIG, see this page, and for NIG this page.) I have found that most coordinates are according to OIG, even in newer publications. I am going to assume we are using OIG. (If not, hopefully the results are so wrong that one can tell right away that they are not OIG. This point highlights the fact that you need already to have some kind of rough idea where the right location is so that you can verify the results.)

The coordinates should have an even number of digits. Sometimes they are divided in half by a space, period, or slash, but other times there is nothing separating the string of digits.

If you are given six digits, then the first three digits give one coordinate and the second three digits give the other coordinate. If you are given eight digits, then the first four are one coordinate and the second four are the other. And so on.

The first coordinate gives the easting position (think longitude or x-axis), and the second coordinate gives the northing position (think latitude or y-axis). In other words, the coordinates give you lon/lat. This is the opposite order we normally use of lat/lon for geographic coordinates.

The first (easting, x) coordinate is actually always six digits. If you are only given three digits, then you need to append three zeros to the right side. If you are given four digits, then append two zeros to the right side.

The second coordinate, on the other hand, can be six or seven digits, and is a little more complicated. For the second (northing, y) coordinate, if you are given three digits, then you have to append a “1” to the left side and three zeros to the right side.

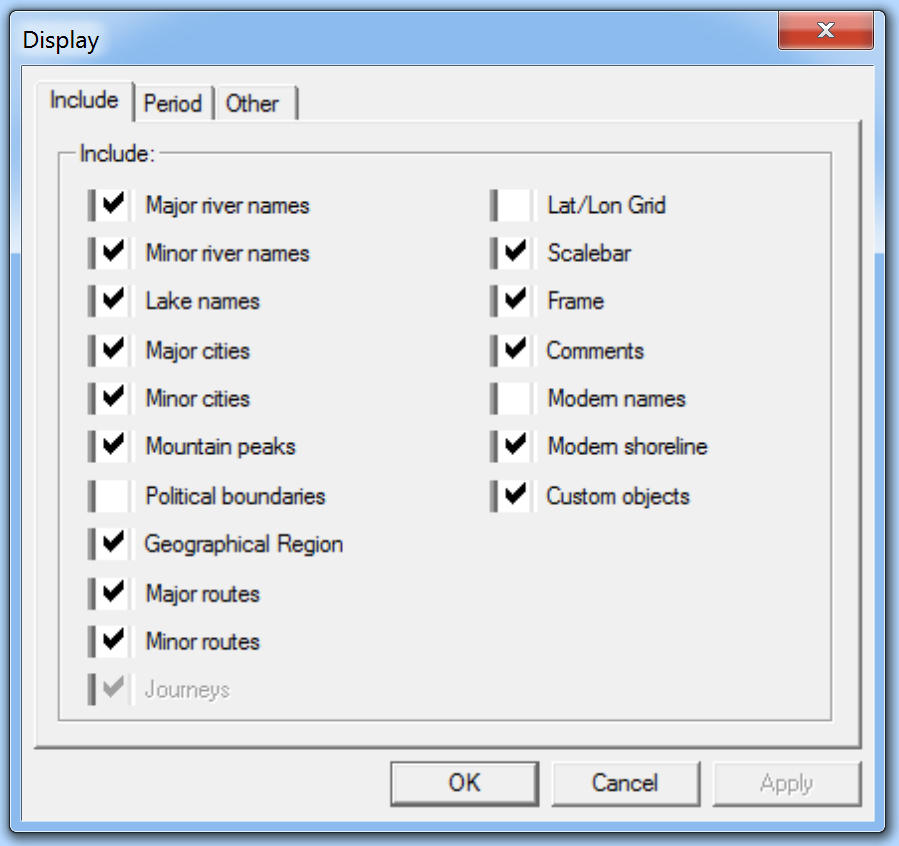

With these expanded coordinates, you can now make the conversion using a fantastic website named “The World Coordinate Converter.” (Thanks to Shawn French for finding this gem.) In the top right, from the first dropdown list, scroll down to Israel and select Israel 1923. This is the Old Israeli Grid.

Then, paste the coordinates into the fields. Below this in the second dropdown list, you will need to select “WGS 84/Pseudo-Mercator.” It is found under *World, which is the first group of reference systems. This is the datum used by Google Earth. Finally, click Convert and voila! you have coordinates that you can copy/paste into Google Earth/Maps.

Here are three examples.

Khirbet Jazzir

- Anchor Bible Dictionary gives the coordinates 219156 for Khirbet Jazzir. This is thought to be the most likely site for the Levitical city Jazer.

- The easting (longitude, x-axis) coordinate is 219. We need to add three zeros to make this a six digit number, namely 219000.

- The northing (latitude, y-axis) coordinate is 156. We need to add a “1” to the left and three zeros to the right to get 1156000.

- Now go to “The World Coordinate Converter,” select Israel 1923, and paste in the expanded coordinates in the same order they were given to us, 219000, 1156000. Make sure you are converting to “WGS 84/Pseudo-Mercator” and click the Convert button.

- The converter generates the following lat/lon coordinates that I can then paste right into Google Earth: 31.996063441518004, 35.728730514891744. Make sure lat is first, and lon is second.

Tell el-Maṣfā

- In an article by Israel Finkelstein, Ido Koch, and Oded Lipschits, entitled “The Biblical Gilead: Observations on Identifications, Geographic Divisions and Territorial History,” it is proposed that Mizpah of Gilead be identified with Tell el-Maṣfā.

- The coordinates given are 227193.

- This gets expanded to 227000, 1193000.

- The convertor returns 32.32932657748971, 35.815608335148326 which can be used in Google to locate the site. (We note that these coordinates do not correspond to the hill that they have marked on the p. 143 photograph. It looks to me like their arrow needs to be moved about 1 inch to the left.)

Finally, I was recently asked to make a map that shows Karm er-Ras in Galilee. The Hadashot Arkheologiyot article for this site gives very precise coordinates for each excavation area, both NIG and OIG. The OIG coordinates for Area A are 181580/239335. These are already six digits, so all I need to do is paste them into “The World Coordinate Converter” to get 32.74860752349965, 35.33387296365357.

The OIG and NIG coordinates are measured in meters. If you are given three digit coordinates, then the accuracy could be off by about half a kilometer. If you are given all six digits, then your accuracy is sub-meter.