There have been a number of articles published within the past few months, all of which are related to the content of this blog.

Galil, Gershon.

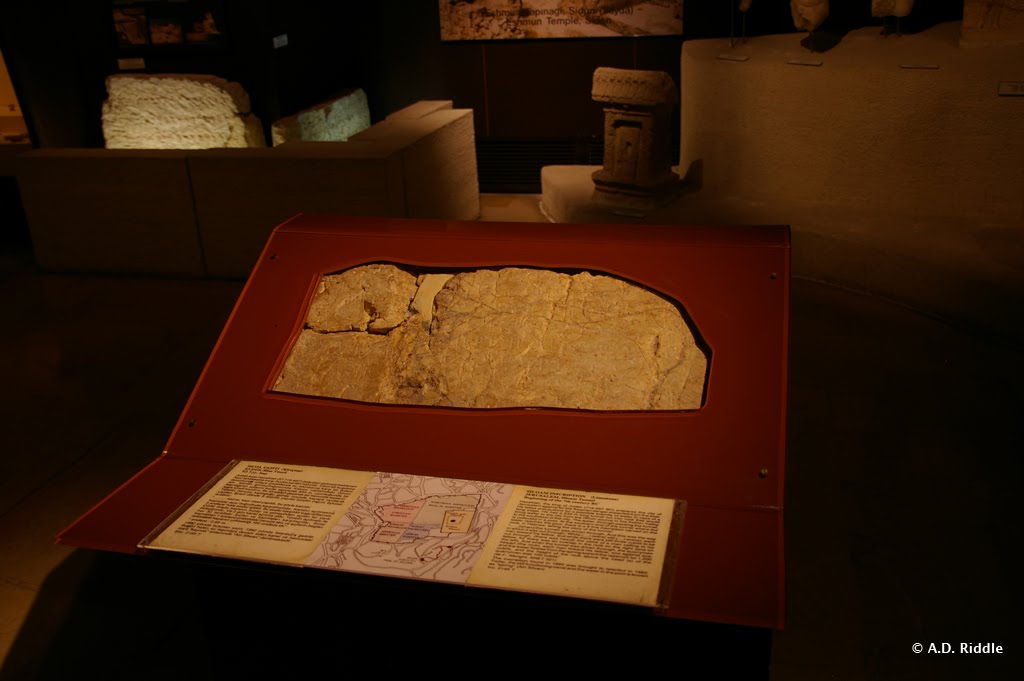

2009 “The Hebrew Inscription from Khirbet Qeiyafa/Neta’im: Script, Language, Literature and History.” Ugarit-Forschungen 41: 193-242.

I have not read this article yet, but presumably this is Galil’s formal publication of his reading of the Qeiyafa ostracon and of his identification of Kh. Qeiyafa as Netaim, both of which were mentioned previously by Todd (inscription and identification).

Beitzel, Barry J.

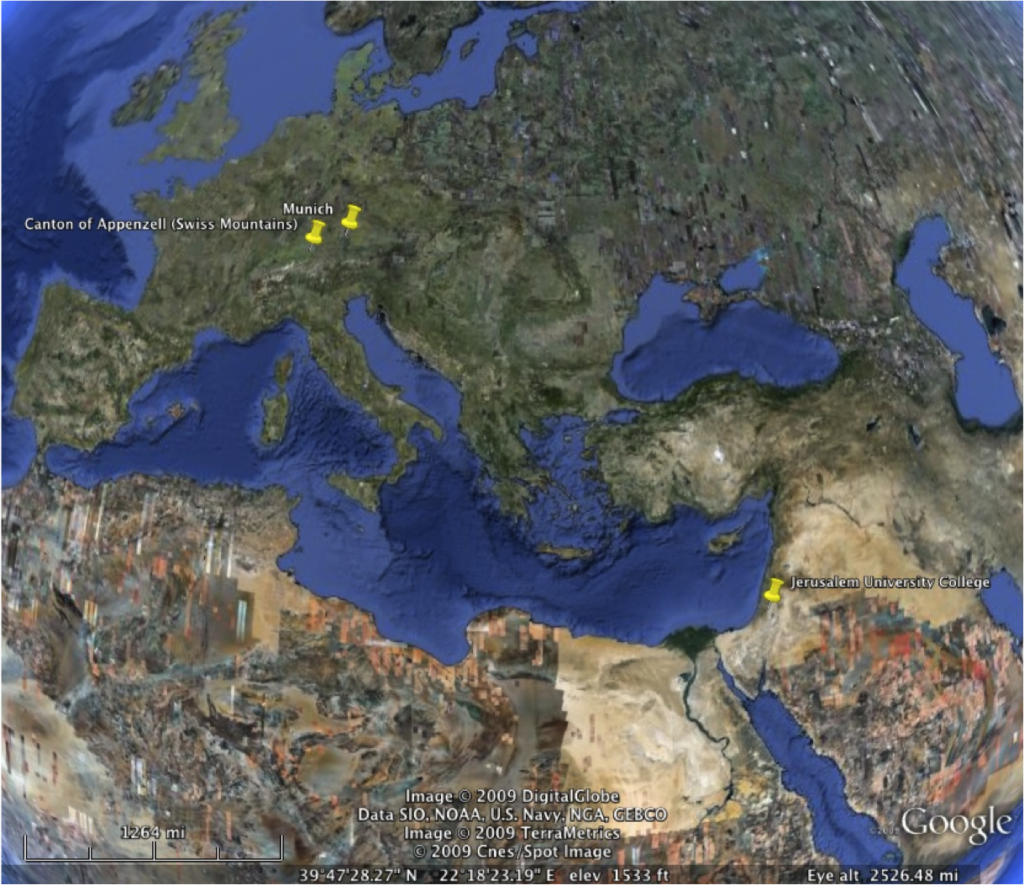

2010 “Was There a Joint Nautical Venture on the Mediterranean Sea by Tyrian Phoenicians and Early Israelites?” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 360: 37-66.

de Canales, F. González; L. Serrano; and J. Llompart.

2010 “Tarshish and the United Monarchy of Israel.” Ancient Near Eastern Studies 47: 137-164.

Both of these articles argue for the plausibility of Phoenician nautical trade on the Mediterranean Sea in the 10th century B.C. Beitzel argues that the Hebrew expression ’onî taršîš in 1 Kings 10:22 is better translated “ships of Tarshish” as in the ESV, and not “trading ships” as in the NIV. He gathers together the evidence for early Phoenician trading on the Mediterranean and suggests Tarshish was located in the western Mediterranean. De Canales et al. identify Tarshish more specifically with Huelva, Spain, and date the earliest excavated levels to 900-770 B.C., while proposing an even earlier Phoenician presence.

The latest issue of Israel Exploration Journal contains three articles which may be of interest to our readers.

Rendsburg, Gary A. and William M. Schniedewind.

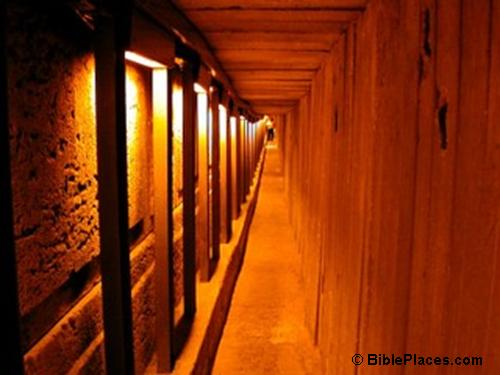

2010 “The Siloam Tunnel Inscription: Historical and Linguistic Perspectives.” Israel Exploration Journal 60/2: 188-203.

Rendsburg and Schniedewind argue that three linguistic peculiarities of the Siloam inscription point to the dialect of the Northern Kingdom of Israel (referred to as Israelian Hebrew). They go on to speculate that the inscription was authored by a refugee from the northern kingdom, and that the purpose of the tunnel may have been to divert water to the refugee population on the Western Hill.

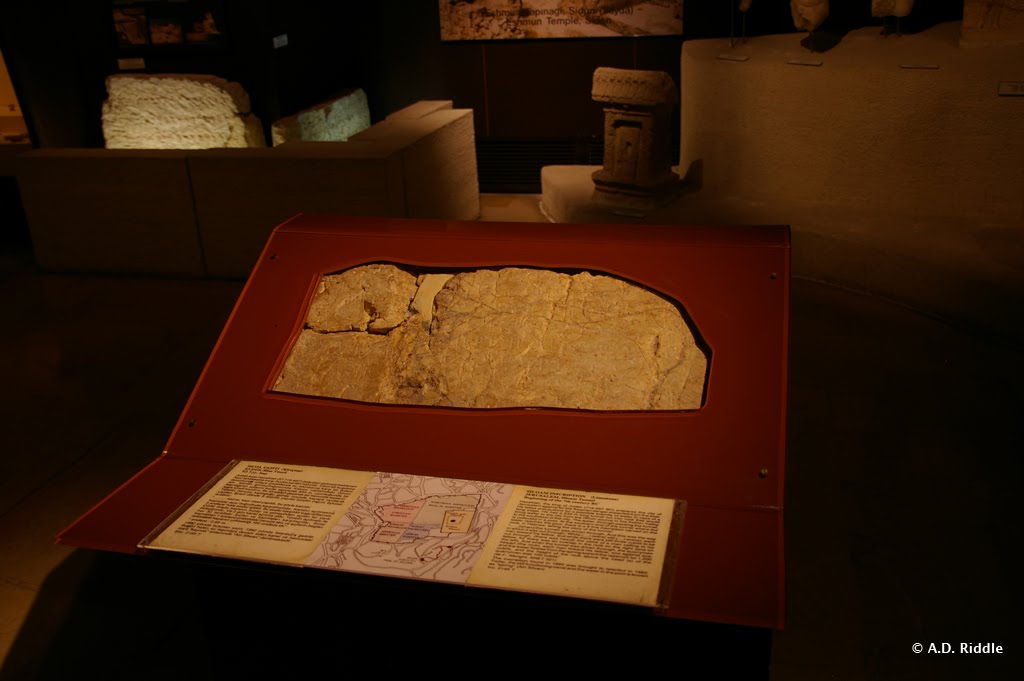

Siloam Tunnel Inscription in Istanbul, Turkey.

Siloam Tunnel Inscription in Istanbul, Turkey.

Two more cuneiform inscriptions from Hazor are published in this issue of IEJ as well, one a fragment of an administrative docket and the other a fragment of a clay liver model. (Neither of these are the tablet fragments found last year that Todd reported on here.)

Horowitz, Wayne and Takayoshi Oshima.

2010 “Hazor 16: Another Administrative Docket from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 60/2: 129-132.

Horowitz, Wayne; Takayoshi Oshima; and Abraham Winitzer.

2010 “Hazor 17: Another Clay Liver Model.” Israel Exploration Journal 60/2: 133-145.

These two inscriptions supplement the handy volume of all cuneiform inscriptions found in Canaan (up to the date of publication), Cuneiform in Canaan: Cuneiform Sources from the Land of Israel in Ancient Times, by Wayne Horowitz,; Takayoshi Oshima; and Seth Sanders (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, and Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2006). We should also add to the list:

Horowitz, Wayne and Takayoshi Oshima.

2007 “Hazor 15: A Letter Fragment from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 57: 34-40.

Mazar, Eilat; Wayne Horowitz; Takayoshi Oshima; and Yuval Goren.

2010 “A Cuneiform Tablet from the Ophel in Jerusalem.” Israel Exploration Journal 60/1: 4-21.