King Ahasuerus promoted Haman the son of Hammedatha the Agagite (Esther 3:1).

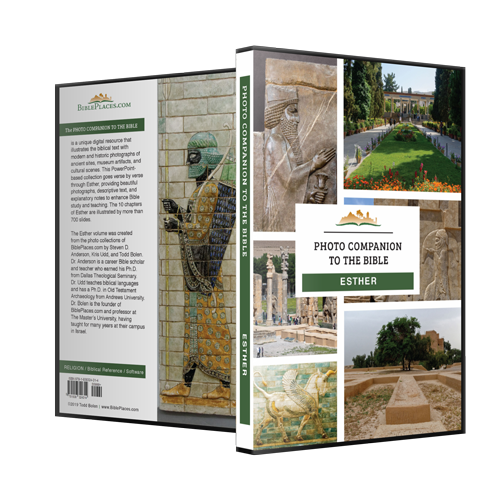

This figure of a Persian dignitary is a relief on the north stairs of the Persepolis apadana. A common view among commentators, both ancient and modern, is that the term “Agagite” refers to a descendant of the only Agag named in Scripture, the familial name of the king of the Amalekites (Num 24:7; 1 Sam 15:8, 20, 32–34). This then provides a reason for Haman’s hatred of the Jews, since Amalek was a descendant of Jacob’s rival Esau (Gen 36:12, 16; 1 Chr 1:36).